Exercises in Historic Confidence. Commentary on the History of the Hnat Hotkevych City Hall of Culture in Lviv

19 May 2019 • Denys Pankratov

In October last year, I participated in the architectural and spatial workshop focused on redesigning the Hnat Hotkevych City Hall of Culture in Lviv. This event held by the administrators of the hall brought together young architects from various Ukrainian universities to discuss the tasks of a functional reinterpretation and project optimization of public spaces of the building. My part was limited to having an interest in the history of building the hall and attempting uncertain tries to interact with others.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

A few years ago, I for the first time stood against the red, almost rusted, frontispiece of this functionalistic building.

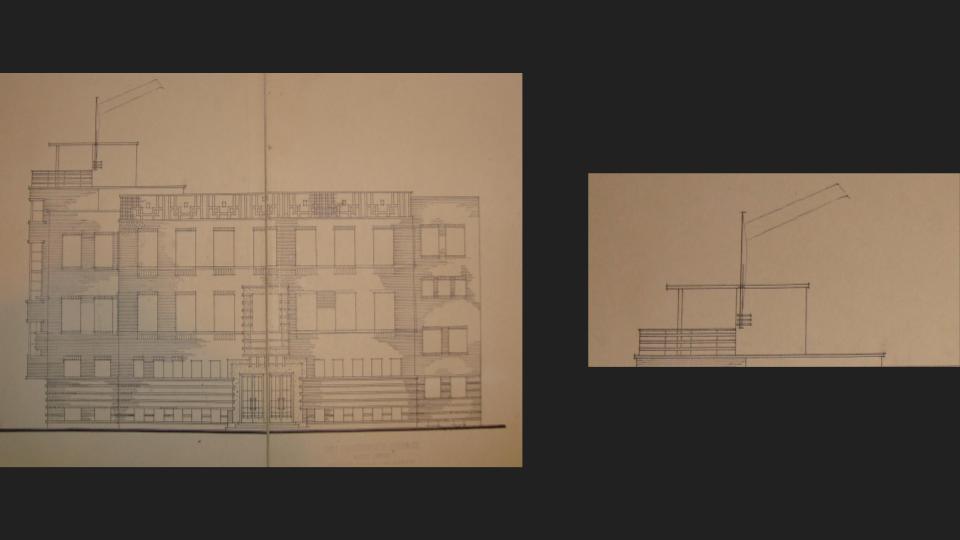

Below (in the basement), there’s a row of dark square-shaped arrow-slit windows, above (on the ground floor), there are steep vertical lines of bulging bricks and the same windows. Under the windows, there are two white lines of the concrete cornice converge to the white concrete bay window with the heavy glass door of the main entrance below it. On the first floor, big windows disperse to both sides of the bay window. The red wall rises up to three storeys and ends in the attic with a brick pattern.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

Above that, I got intrigued by certain passages from the history of the construction of the hall which were printed on the glass sign near the entrance. They were about the 1924 labour strike when the trade union of Lviv communal workers decided to raise funds for constructing a building for the workers’ needs. During several years, members of the trade union were sacrificing 1 per cent of their salaries and finally, around 1933, they ordered architectural design and started construction. They were doing it on their own, during off-work hours and weekends. In 1934, the worker’s house started functioning. Informally, the building was called ‘The Red Fortress.’[1]

It was a common practice of creating the environment, a vision of one’s own free time, and a practical and architectural assertion of it by workers of that time who didn’t have any power over their time at all. And the interest to such a gesture of self-management supported the idea to get to the hall’s archives.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

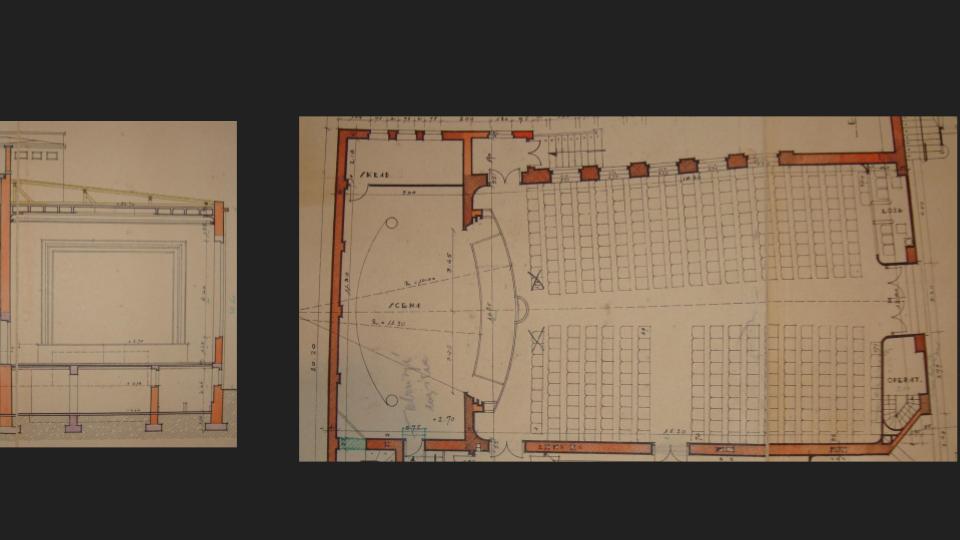

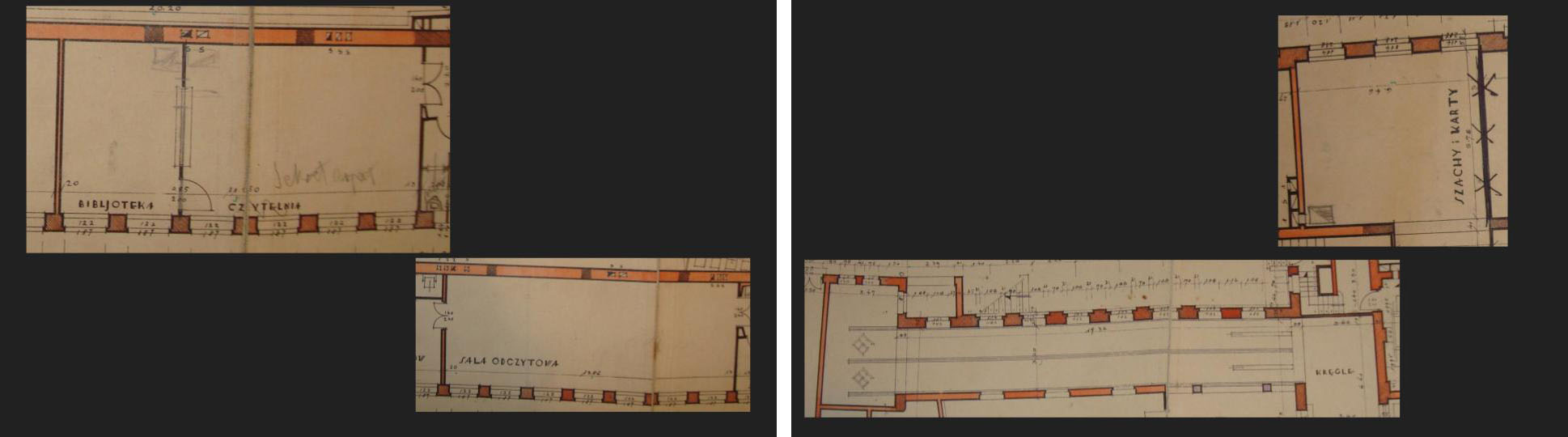

The first thing I learned at the workshop was that the hall didn’t have its own archive, much less from the interwar period. However, for working with the history of the hall, the architectural plan of the building designed by Tadeusz Wrobel and Leopold Krasinski was found in the city archives. Working on re-designing the hall, workshop participants used this original layout of the premises as a reference to a great extent, comparing it to Soviet and post-Soviet changes done to the building’s space.

We don’t know much about the changes themselves, only that there was a considerable extension during 1976-1980, as former and current hall workers tell.

Besides, certain documents – representational catalogues of the Soviet era – are left here.[2]

The decision to look into the Soviet archive first was developed in the light of a short but representative discussion among the workshop participants. Wondering how authentic were the interiors and what reasons and meanings stood behind the materials the hall was decorated with, we came to two different points of view.

One tended to reduce the interior to the original style of the building – modernist functionalism of the beginning of the 20th century. Another one gave some symbolic meaning and historical value to soviet tuff and brick columns with which walls of the hall are filled.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

That material, the Armenian violet tuff, the Baltic brick from the beginning of the 1970s, found to be the closest to the original brick. There was also the red stone with a floral pattern carved on it; fragments of the white stone bulging from brick walls; brown ceramic tiles with a radial pattern; textured gypsum tiles; a gypsum panel with a bas-relief of a medieval city; a panel with spruce scenery made of multi-coloured stone; a bronze frieze on the wall.

And more: the Armenian tuff coloured in blue; recently laid brick on the fragment of the column; ceramic tiles covered with yellow film; a gypsum bass-relief covered with orchry enamel; faded wall fragments showing under moved around pieces of furniture...

Workshop participants noticed this disunity and fragmentation of the space, as well as its fatal collage nature. It was this questionable, flimsy design on the line between the Soviet and post-Soviet attitude to space, this jumbled historical dialogue between terrains and surfaces, this failed palimpsest that was that important historical junction, hardly noticeable in the inter-war history of the hall. It connects space and its architectural history with the reality of human relationships – uncontrollable practices, both individual and communal, of exploring, (re)appropriating, and (re)inventing this architecture.

At the same time, the contrast of a modern state of hall’s interiors, which gives evidence of human presence, makes the image of those who ‘were here before us,’ who founded, constructed, and developed this building, more and more washed out – this image gets decomposed in rusty bricks of a frontispiece and gets scattered among the archives.

Below, I will comment on what the eye sees, the eye eager to find and assert human presence on a faded representation area.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

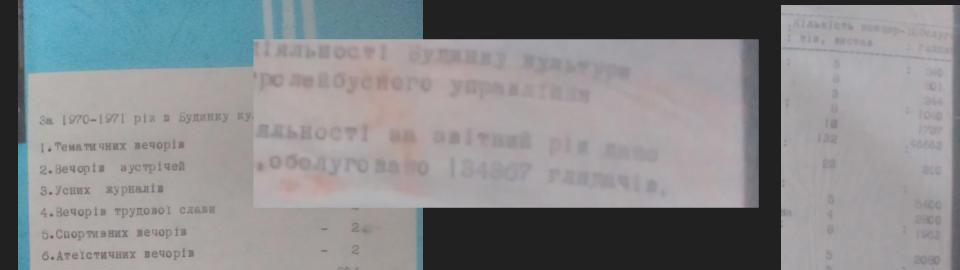

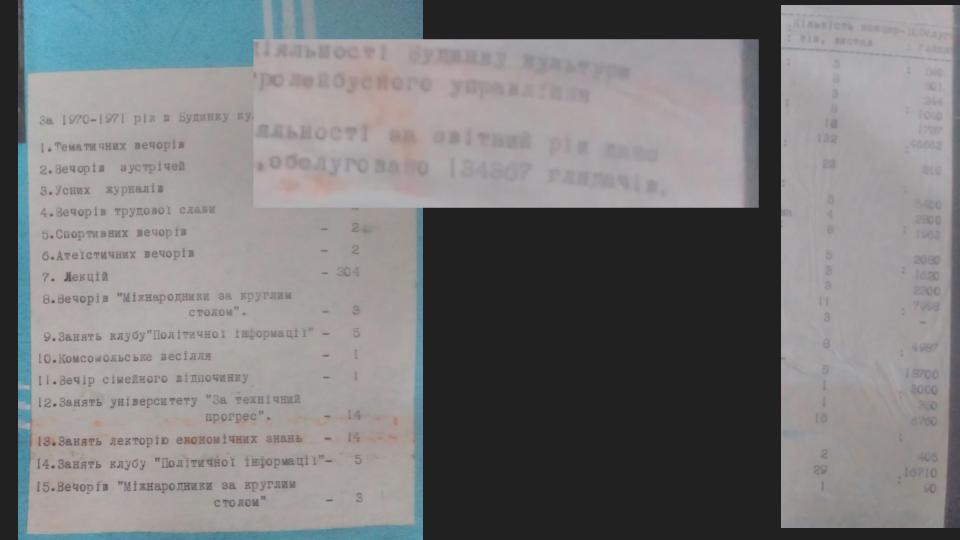

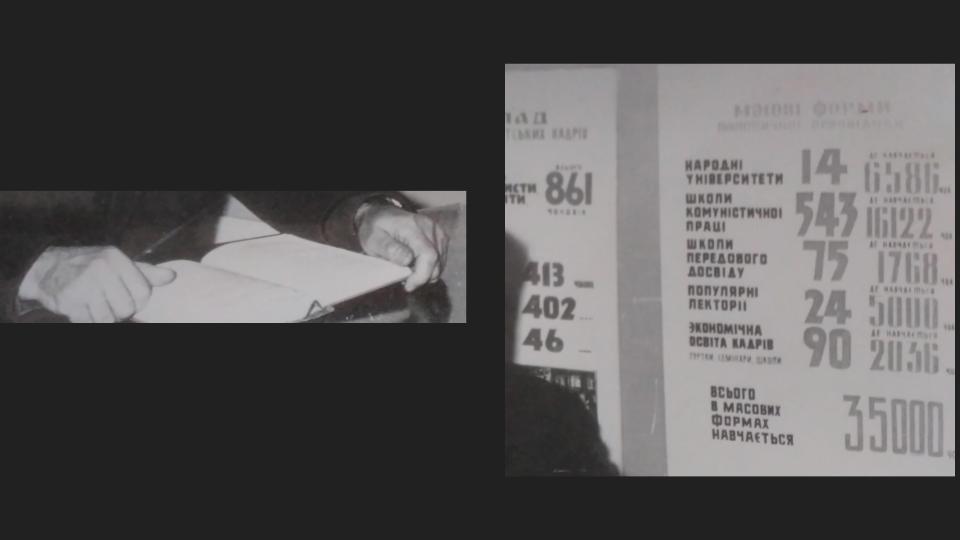

One of the Soviet albums with some documents from communal work in 1970 at the Cultural centre of the Lviv Tram and Trolleybus Administration (LTTA) called ‘Mass and Political, Cultural and Educational work of the LTTA’ is dedicated to Lenin’s day of birth.

The photograph which opens the album is placed inside the sheet. We see a bright room showing from open doors, four little tables in the middle of the room, with two chairs facing each other around each table, and the TV above the last, the most distant one. The TV is off, the light flares from windows, there is no one in the room. The photograph has a caption: ‘The lounge room.’ The next page contains a graphic image of the building, the way it was before the development. In the foreground, under the wall, there’s a trolleybus, a flag flies on the roof of the bay window, a rectangle with someone’s portrait is placed above the main entrance. Various samples of pocket-sized booklets, lecture programs, invitations, schedules of themed meetings, etc. are glued up on the next pages. Finally, we see the first faces – figures and side-faces – canonically smiling, turned to the right margin, outside the image.

Does the nature of these faces correspond to the faces of real people these images are addressed to? Did those people take something from these portraits? Or it was left to be an iconographic construction, not relevant to human reality?

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

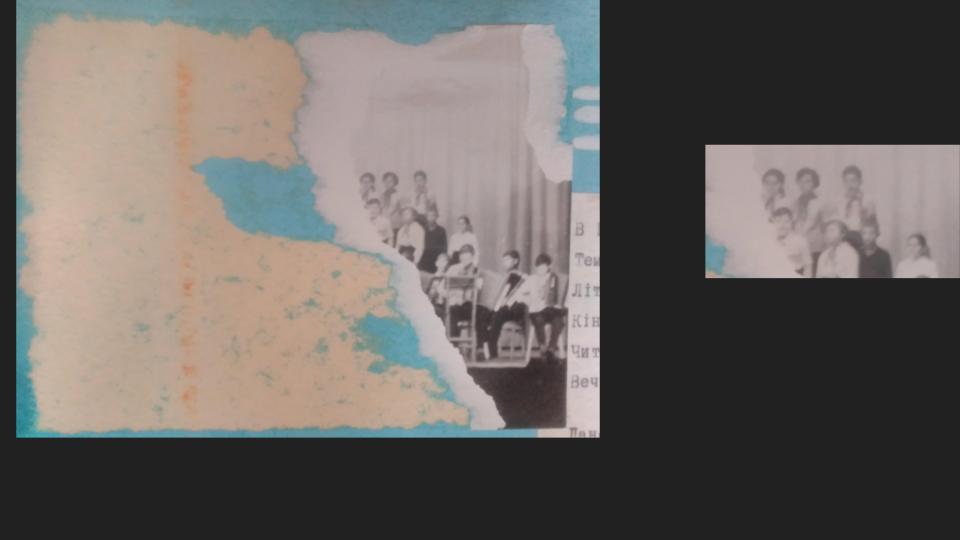

The stage is nearly the only place Soviet documentation refers to. It’s the unified, bright space where all organized forms of leisure are concentrated: the symbolic certainty of group figures, their clothes, choreography, particular gestures, endless, unchangeable smiles. The view localized by the stage eliminates eventuality and hides everyday routine in the darkness of audience seating.

I stumble upon the page with a caption ‘Child Choir Collective (the conductor – Selezniova).’ There is a small fragment of a photograph above – the biggest part of it was torn out. On that fragment we have left with, we can see some kids performing on the stage. The quality of the photograph doesn’t allow us to examine the faces, we only see dark shapes of hairstyles and hats.

The sheet with figures about the collective’s activity during 1970-1971 (types of performances, geography, the number of visitors) typed on a typewriter is glued near the photograph.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

In the middle of the catalogue which represents a Moscow tour of different collectives of the hall in 1960, we find a photograph, folded in two parts. On the left part of it, we can see the stage and a singing man on it. There are four men with musical instruments behind him; women with their heads covered sitting next to the stage; other listeners gathering behind, surpassing a long, bright corridor on the background. On another part, which was folded, we see a microphone under the stage and a tabouret with a tape recorder on it. A woman is sitting next to a tabouret, holding earphones. A small fragment of dark floor separates the audience and the stage. Young and old women with their heads covered, wearing cotton-wadded jackets and fur coats, and men wearing caps are sitting at the first rows. There’s a man wearing a work apron in the middle of the first row. Workers are standing and watching the stage from the third row and further, peeking from behind the shoulders and heads of their colleagues. On the top of the frame, we see a white cloud of hands placed on the knees and a row of legs hanging from high window stills.

The event takes place inside the working space of one of the Moscow factories.

‘The anti-fascist congress of the cultural workers took place in this building on the 16th of May, 1936,’ says a grey table hanging on the wall of the hall.

Here’s the page from the newspaper ‘The Labour Tribune’ from the 24th of May, 1936.[3] The congress coverage. Bright spaces among the compactly printed columns are marked in the middle with the sign ‘Confiscated!’

The coverage ends with a manifestation which appeals to indefatigable mothers, starving villagers, bakers, construction workers, stonecutters, typographers, railmen, miners, Jewish students, sailors, soldiers who ‘were tired of a long-lasting march,’ to ‘everybody who wasn’t afraid to think and speak.’ This manifestation ended with the following phrase: ‘We are not looking for new sources of inspiration among you, exhausted; we want to celebrate the greatness of a common goal with a strong word. This is a virtue of human fate.’ A dimmed picture on the page has a caption: ‘The photograph of the participants of the Congress of cultural workers in Lviv.’

There are several rows of human figures and it’s hard to identify somebody among them. We see white blurs of faces and collars, hands up front, a couple of bright jackets; a woman with a white bow is sitting in the middle; another woman, standing, wears a white shawl on the shoulders.

White lines of a concrete ledge above people extend to the bay window where we see a dark front entrance. Above people, there are dark arrow-slit windows of the first floor in among the brick terrain.

It could be that one of the women was Anna Kovalska who announced the manifestation. It’s highly likely that there are, among others, faces of Wanda Wasilewska, Halyna Gorska, Stepan Tudor, Oleksandr Gavryliuk, Yaroslav Galan, Kuzma Pielechaty, Karol Kuryluk, Leon Kruszowski and other cultural workers and political activists of Lviv at that time.

This event was later well documented by Soviet historiography and solidly incorporated in the Soviet narrative of the reunion of Western Ukraine and the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic as the exemplary party action.

The note by Halyna Gorska, published in the art magazine ‘Signals’ from June 1936, allows for deviating from the big history of flaming speeches and unanimously taken resolutions, dragging our gaze away from the figures on the stage.[4]

She speaks of Lviv of that time ‘where there still are echoes of horrible April days.’ Of Lviv ‘which suffers and revolts, which is tortured but still fights.’[5] The note tells about the workers ‘with hungry and feverish eyes,’ who were gathered near the entrance to the Centre of community workers. It tells about the ‘the burden of indignity’ those people carried on their shoulders. It tells about the strike of construction workers and their delegate who had to read the strike news to the Congress.

This note is not simply a newspaper report but also a critical comment addressed to those writers of the Congress who, without much doubt, put this suffering and rebellious sublimity of workers, their support and approval of this event, into the agitational quality of their poems.

Writing about her impressions of the Congress, Wanda Wasilewska recollects a truly specific, unique moment when two thousands of people, all to a man, answered the question from the Bronevsky’s poem, ‘Are you ready?,’ with ‘We are ready!’

But this moment doesn’t have to be the moment of the exhilaration of the power of their word alone.

This should also be a moment of realizing a great responsibility we have on us.

We should offer them not only our arm and our word needed in struggle.

There will come a moment when it will be them and not us who will ask: Are you ready?

And we have to answer: We are ready!

This is a view which is placed somewhere under the stage – on a little space among the first rows. It grasps the dynamics of common admiration of those who perform and those who listen.

Finally, this note allows getting closer to the story which initiated the building’s construction. It is the ambiguous evidence of how relations were established. The relations between those who produce a cultural product and – possibly, for the first time ever – those who are its end users.

In the architectural project planned by Wrobel, there was the stage at widths of 11 metres, the 350-seat hall, and the 170-seat balcony, along with cloakrooms, a snack bar, and toilets. There were locations designed for playing chess and card games, bowling lanes, a library, a reading room, a room for lectures, and a smoking room.

On the layout of the frontispiece, there’s a flag on the bay window.

[1] To find out more about the history of the Hnat Hotkevych City Hall of Culture in Lviv, visit the following websites: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/uk/organizations/16-dim-robitnykiv/ https://lia.lvivcenter.org/uk/objects/kushevycha-1/

[2] Representational catalogues of the Soviet era are dedicated to various symbolic events of the Cultural Centre of the Lviv Tram and Trolleybus Administration, or ‘tram workers’ club’ as it was called until 1980, and the Hall of Culture of Workers of the Kuznetsov Communal Service, unofficially named ‘Kuznechik’ during 1980-1996. Among them, there were the following catalogues:

● ‘The Folk Dance Ensemble of the LTTA Club – Featured in the Movie ‘Songs Over the Dnipro’,’ 1956

● ‘The Performance Report by the Folk Dance Ensemble of the Hall of Culture of the LTTA before the Workers of Moscow,’ 1960

● ‘The Seventy-Fifth Anniversary of a Tram,’ 1969

● ‘Mass and Political, Cultural and Educational Work of the LTTA,’ 1970, dedicated to Lenin’s centennial

● ‘The Hall of Culture of Workers of the Kuznetsov Communal Service,’ 1980

● one post-Soviet nameless event log of 1995-1997

[3] You can find a fragment of the newspaper in the article published in the Polish magazine Lewacka Sztuka: http://lewackasztuka.blogspot.com/2018/09/lwowski-zjazd-pracownikow-kultury.html

[4] Sygnaly №18, ‘Pisarz i Masy’ by H. Gorska: https://polona.pl/item/sygnaly-sprawy-spoleczne-literatura-sztuka-1936-nr-18-1-czerwca

[5] It is referred to workers’ demonstrations in Lviv in April 1936. During the demonstration, the police killed one of the participants – Maksym Kozak, following which protests burst out with a vengeance and didn’t stop until May. For more details, visit the following website: https://lia.lvivcenter.org/uk/events/vladyslav-kozak-funeral/

–

Denis Pankratov is an artist, researcher and co-founder of the Method Fund

–