A steppe with rabbits and pheasants running around, and where some even saw foxes

25 October 2019 • Daryna Mamaisur

Last autumn, I happened to travel for nine hours by bus from Lysychansk to Mariupol. The bus route ran through the line of separation, a territory marked as the control zone at the first checkpoint. This was one of the first times I travelled to Donbas, and my excited and amazed eye, I'm sure, was similar to the eyes of those who witnessed the region’s intensive industrialization over a hundred years ago. Rough terrain, creeks and hills emphasized the vastness of the expanses where giant industrial buildings occasionally emerged. At the same time, it was an excitement you would immediately want to put in doubt and undermine because of its naivety and shallowness. This inner contradictoriness inspired the exploration of symbolic oppositions around the (non)industrialized landscapes of Donbas.

The Donbas landscape experienced radical transformations at the end of the 19th century: workmen’s settlements, railroads, and new industrial objects such as an ironworks and a mine were emerging back then in a sparsely populated steppe. These landscapes, together with daily life in the region, is depicted in travellers’ and temporary workers’ observations, often conflicting, and in working-class folklore. A big number of Donbas workers were former peasants for whom a mining job was not only a new working discipline but also another interaction with the land: working in a confined space, without light and fresh air, interference in the depths of the earth and coal production were considered a sin. Some contemporaries described the world of the technical progress with enthusiasm: “Travelling through these parts, you would see lots of factory chimneys sticking up and belching smoke, mine headframes everywhere on the horizon, while at nights, the glow of blast furnaces which smelt ore could be seen in all directions…” (Vasyl Babenko, ethnographic report of 1905)

However, workmen’s settlements were repeatedly described as sombre and monotonous places which lack comfort conditions for work and rest: “…the mine and its intentionally prosaic environment, which so doesn’t fit the spring steppe, could spoil this beauty, especially large piles of stacked up whitish-grey rocks, stinking with sulphur being burnt, where the outlines of people were always puttering around in the whitish smoke, handling mine carts. I remember a strange feeling of imprisonment that often came upon me during the first years of service on mines, especially strong in spring… I felt an ardent desire to escape and excruciating anguish...” (reminiscences of a mining engineer Oleksandr Fenin, the latter part of the 1890s)[1].

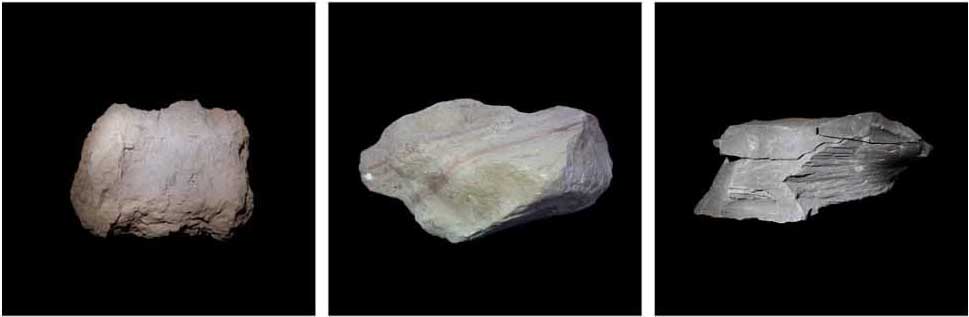

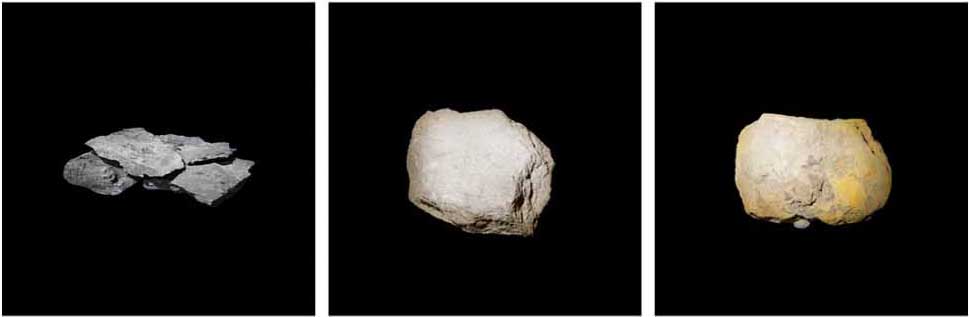

A new landscape was often described as opposing a wild and picturesque steppe, a so-called Wild Field, which was here long before the emergence of heavy industry. Such an opposition around the landscape transformations is characteristic not only of Donbas but of many industrial cities in the world, for example, Southern Wales where “lovely and fresh valleys, covered with summer fog,” were put in opposition to ugly spoil tips, fearsome black furnaces, chimneys, and wagons loaded with coil. In art studies, there’s a critique of coil as both art object and material: coil displays its useful properties only after being burnt, in other words, being destroyed; it's evenly black and doesn’t give any visual, olfactory, or tactile pleasure, as compared with wood, marble, stone, leather, or paper [2]. But despite this, these regions didn’t become less attractive to travellers. The genre of industrial landscape was growing in popularity in photography: many of such are on postcards of that time. Indeed, spoil tips were actively incorporated into Soviet propaganda – they became the marker of industrial cities and were depicted on guides, postcards, and emblems. However, their image had value only as long as it concealed its “unwholesome” nature and functioned as a substitute for “natural” picturesque slopes.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

The ambivalence also characterised the perception of coal itself: it combined admiration, that came from acknowledging the value and impact on the state economy, and fear caused by dangerous and risky working conditions. The Soviet propaganda of the 1920-30s builds itself on these exact oppositions: it aims at the heavy industry development and the idea of human mastery over nature. It forms a tradition of overtime work and record-breaking performance, putting a heroic and loyal shock worker in the limelight.

I think of Martin Pollack’s text Tainted Landscapes in the context of exploring landscapes. But unlike him, I don’t want to reveal or point at what was hidden and kept silent for a long time. Instead, I wanted to see a landscape as a symbolic construction around which a symbolic dimension, expressed in language and linguistic structures, is built. To what extent a modern language is led by and reconstitutes formerly created oppositions? One visitor of the Lysychansk Museum of Mining History, a woman in her 50s, shared a story with a museum worker: “My grandson had recently found a lump of coal somewhere on the street and brought it home. It looked so nice you would want to lick it. Shiny. Polished. Beautiful.” Here are some other observations I’ve heard in Lysychansk: “Our coil is light as wood. Anthracite, on the other hand, is very different, expensive” (Nikolai, activist, Lysychansk local history club member); “For miners, everything that isn’t coil is waste rock,” “You’d better come here in September. Now, it’s off-season. In September, there’s a little spoil tip near every private house” (a local locksmith who refused to introduce himself). The current opposition combines official nostalgic pathos and glorification of labour with the rhetoric of the region’s ecological exhaustion and terrible working conditions. The name of this essay and the accompanying archive quotes word for word from the Google Maps review of some industrial establishments in Ukraine. It is kind of a modern-day response to the information from the 19th century, which also brings voices of city residents and factory workers together.

For example, Daniil Gromov wrote about the limited liability company Kramatorsk Metal Construction Plant a year ago (original spelling retained): “The money’s no good, no tools and uniforms. But unlike the NKMZ, there’s fresh milk every day! On the NKMZ, they didn’t give a damn thing but boots made by DNR prisoners and a uniform!” Finally, a review of the Azovstal Iron and Steel Works written by Volodymyr Zhdanov a year ago reads as follows: “The Azovstal is gradually turning into a steppe with rabbits and pheasants running around, and where some even saw foxes.”

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

[1] Portnova T. Landscapes of Donbas, in Work, exhaustion, and success: industrial monocities of Donbas, ed. by Kulikov V. and Sklokina I., Lviv, 2018.

[2] Price D. COAL CULTURES. Picturing Mining Landscapes and Communities, Bloomsbury Publishing Plc, London, 2019.

_

Other than specified, the text uses the following sources:

Studenna-Skrukva M. The realm of coil and iron. The role of industrialisation in the process of social transformations in Donbas. In in Work, exhaustion, and success: industrial monocities of Donbas, ed. by Kulikov V. and Sklokina I., Lviv, 2018.

Kulikov V. Industrialisation and Transformation of the Landscape in the Donbas from the Late Nineteenth to the Early Twentieth Century, in Zuckert M., Hein-Kircher H. (Eds.), Migration and Landscape Transformation. Changes in East Central Europe in the 19th and 20th Century, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht LLC, Bristol, CT, USA, 2016.

–

Daryna Mamaisur is a Kyiv-based visual artist and researcher. Balancing between writing, photography, and filmmaking, she addresses issues of public space and its transformations, memory studies and visual culture in her work.

–