A sack, farce, and nationalism: the image of anarchists in soviet and post-soviet cinema

10 June 2020 • Mykola Ridnyi

I’ve watched ‘The Elusive Avengers’ film saga multiple times. Directed by Edmond Keosayan, this ‘Soviet western’ is set in the Kherson region during the civil war of the 1920s. Adolescent characters – a group consisting of a shy city kid, brave siblings from the village and their charismatic ‘gypsy’ friend – were exacting revenge on adult oppressors and looked extremely attractive for the preschool-aged viewer. The oppressors were cruel and conservative petty tyrants of vague political views portrayed as mobsters. It wasn’t until very much later that I learned that anarchist Makhnoites were shown as ‘gangsters’ and that this ludicrous cliche migrated from one film to another across the decades.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

I started researching the image of anarchists in Soviet and post-Soviet (Ukrainian and Russian) cinema in 2015, while preparing to make my own film ‘Grey Horses,’ dedicated to my great grandfather, anarchist Ivan Krupskyi. He led a rebel group in the Poltava region and during a certain part of the war, was fighting at the side of Nestor Makhno, against both white royalists and Bolsheviks.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

«Gray horses», Mykola Ridnyi (trailer)

Image caption: Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

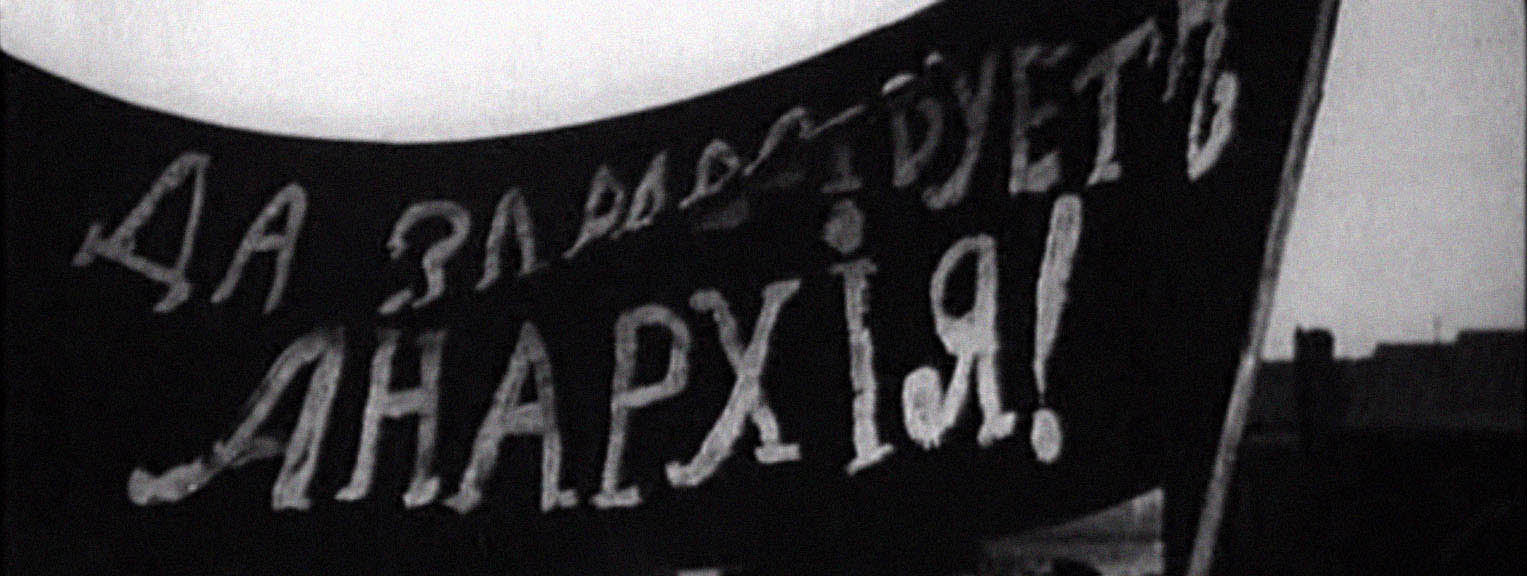

The first appearance of the anarchist character in Soviet cinema dates back to the 1923 silent film by Ivan Perestiani ‘Little Red Devils.’ ‘The Elusive Avengers’ (1966) was a remake of this film. The characters are practically the same except that the Red Army group in ‘Little Red Devils’ included a black American instead of a gypsy. In the film, he escapes the slave capitalism and joins young fighters for the ‘bright future’ in the ranks of the Red Guard. Abstractly portrayed atamans have concrete political views here: they are Makhnoites and have a very specific leader, Nestor Ivanovych Makhno. At the time of the film’s premiere, after the end of the civil war, Makhno was serving his time in a Warsaw jail and at some point tried to kill himself. It’s possible that he hadn’t seen this movie even after emigration. At the end of the ‘action movie,’ Red Army men capture him, put him in a sack and take to the square for public humiliation. A dehumanized person that shifts into a moving object (in the film, the sack maintains resistance and shoots the attackers) becomes a stereotypical figure for other films on the subject. A sack with an anarchist captured inside is a metaphor of excluding anarchism from a serious academic discussion in the Soviet and post-Soviet space. [1]

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

In the Leonid Lukov’s film ‘Alexander Parkhomenko’ (1942), ropes serve as means of symbolic revenge on Bolsheviks: anarchists tie up their opponent, Parkhomenko. Then it turns out that ropes were used only for highlighting the character’s strength: he breaks the ropes and escapes.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

Sack and rope

‘The Optimistic Tragedy’ by Samson Samsonov (1963) is probably the only movie dedicated to the Kronstadt rebellion of anarchist sailors. A sack appears as a murder weapon here: a man is thrown overboard in a sack. The director uses propaganda to criticise the principles of collective decision-making and people's court, focusing on anarchists’ cruelty and recklessness. Characters mistakenly put to death their fellow and then an innocent old woman. A young female commissar represents a ‘moderate and forced’ chain of command that is opposed to a ‘sloppy’ flat organization among the anarchists.

Other films made during the Khrushchev Thaw also have the emancipating image of a strong woman (Larysa Shepitko’s ‘The Wings,’ Aleksandr Askoldov’s ‘Commissar’). This image shifts the standards of ‘weak’ and ‘strong’ characters in Stalinist cinema and makes the propagandistic nature of the film more complex.

An episode from the Aleksandr Mitta’s ‘Shine, Shine, My Star’ (1970) looks like a directorial reference – possibly not intentional – to a sack in ‘The Little Devils.’ We can see how a metaphor of a sack as a trap is embodied in a huge theatre curtain that traps not just one person but a whole anarchist unit. The action takes place on a theatre stage from where anarchists planned to shoot the audience, and the theatre is located in an over-equipped room of an orthodox church. What we see is how a huge moving piece of cloth – that in such a place looks like a poltergeist or some other evil spirit – is being attacked by people armed with sticks and stools. As a Polish researcher Anna Lazar writes, “The transition from a sack to a curtain is connected to the change in the household. When a sack was no longer a usual household item, it was used for neutralising anarchists.”[2]

Оn whose side?

Surely, ‘the sack and the ropes’ are symbolic, yet not always intentional, director’s motive in depicting the relationships between political opponents. The common Soviet-cinema image of an anarchist is quite unequivocal though: an anarchist is usually a cheerful but brutal criminal type who seeks profit and is politically ignorant. It’s a grotesque image of an ‘armed clown.’ Anarchism is depicted as chaos and farce that always ends not to the benefit of the people involved in it, and this image still remains a cliche. Although, some charismatic anarchist characters don’t serve the interests of a propagandic idea. In the analysis of ‘Aleksandr Parkhomenko,’ Ukrainian historian Sergii Yekelchik states the following: “Even though Makhno is shown as a betrayer and a vicious enemy, he comes out as more psychologically congruent than Parkhomenko. Makhno and his followers were endowed with several popular mass culture melodies. At the beginning of the film, young and dashing anarchist sailors are dancing to the song ‘Yablochko’ (Little Apple) and then strike into ‘Tsyplionok zharenyi’ (Fried Chicken). These two songs were extremely popular in urban street culture.” [3] Same with the ‘pirate’ image of Popandopulo, ‘gang’ member in ‘Wedding in Malinovka’: despite being a negative character, he became one of the favourite comedy characters for the late-Soviet viewers.

The grotesque nature of anarchist characters and the othering of anarchists didn’t end along with the collapse of the USSR. In Sergei Bodrov’s ‘I Wanted to See Angels’ (1992), the image of anarchists is projected on bikers and the soundtrack includes a song by ‘Mongol Shuudan’ called ‘Anarchy.’ This rock band became popular thanks to their ‘anarchist’ image even though they couldn’t be politically identified as anarchists: while glorifying the ataman movement and promoting its aesthetics, they actually relied on the simplified visual images of Soviet propaganda.

The protest and the farce

How does Soviet and post-Soviet cinema show political views of anarchists? Theories of anarchy, clearly enunciated by Kropotkin and Bakunin, are usually replaced by an over-simplified understanding of the absolute freedom that verges upon cannibalism (1965 ‘An Extraordinary Assignment’ and an episode from the 1977 series ‘The Road to Calvary’). The focus is often put on their political uncertainty, their wish to conform and gain profits. Or, anarchists are shown in the political alliance with those who were their rivals in real life: white royalists, German invaders, or church members. But from today’s perspective, the most peculiar aspect of that ideological manipulation is the accusation for being nationalists. In ‘Aleksandr Parkhomenko,’ Makhno expresses his thoughts about an ‘independent mother Ukraine,’ while his opponents say that “Makhno will shortly write a Petliurian Universal Act.” Despite forming an independent anarchist state Huliaipole, mainly consisting of Ukrainian villagers, creating a non-hierarchical and supranational society was his priority.

Besides, Makhno’s village-centred anarchism wasn’t the only anarchist movement at the time of the civil war within the territory of present-day Ukraine. We can also mention urban groups of The Nabat Confederation of Anarchist Organizations. Anarchist views sound not only anti-Bolshevist but also totally anti-capitalist and anti-nationalist – maybe that’s the reason why after 1991, anarchism was still being excluded from the politics of historical memory in both Russia and Ukraine. During different time periods, anarchists were portrayed as anybody but anarchists. In Oleksandr Yanchuk’s film ‘Simon Petliura's Secret Diary’ (2018), Samuel Schwarzbard, Petliura’s killer, is shown as a Soviet spy recruited by Bolsheviks. Following the logic of a new Ukrainian political conjuncture, only a Bolshevik or their ally could kill a nationalist, but Schwarzbard was a committed anarchist and petliurians’ enemy who took revenge for the anti-semitic outrages.

At the same time, Makhno’s image has been actively appropriated by Ukrainian right-wing groups. Accents put on the ‘love to the homeland,’ and the ‘khutor culture’ played a significant role in adapting anarchists to the right-wing populist politics of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance chaired by Volodymyr Viatrovych, as well as to the narrative of far-right ‘creators.’ For example, in ‘Post-traumatic rhapsody’ (2018) written by Dmytro Korchynsky, ex-head of the Counter-Narcotics Department of the National Police Illia Kyva plays Nestor Makhno who exclaims “Glory to Father Makhno!” and “Glory to Ukraine! Death to the enemies!” The nationalist image of Ukrainian anarchists has migrated to the modern-day right-wing agenda from nothing other than Soviet propaganda. A sack put over anarchism almost a century ago made it the signified without the signifier, a substance deprived of its position and therefore turned into means of manipulation. Years have passed, political paradigms and challenges have changed but certain stereotypes have stayed the same and certain ideas have remained inconceivable.

–

[1] Oleksandr Teliuk, Delusive Museum of Oblivion. Mykola Ridnyi. Wolf in a Sack. Galeria Arsenał, Białystok, 2019.

[2] Anna Lazar. Wolf in a Sack. Mykola Ridnyi. Wolf in a Sack. Galeria Arsenał, Białystok, 2019.

[3] Sergii Yekelchik, ‘Oleksandr Parkhomenko’: Donbass Hero in Military Stalinist Cinema. The Cinematographic Revision of Donbas 2.0. Dovzhenko Centre, Kyiv, 2017

–

Mykola Ridnyi – artist and film director, author of texts about art and society, lives in Kyiv. Co-founder of the group SOSka, co-editor of the Prostory.net.ua

–