Two Editions of the Socialist Vision

25 October 2019 • Mariia Tkachenko

(How Socialism Transforms the Industrial Novel)

THIS IS A SAMPLE HEADING STYLE 1

Current Ukrainian landscape in many ways is shaped by industrial objects, mythologemes of which were built in the 1930s and supported until the dissolution of the USSR. Within the first Five-Year Plans, lots of factories were built and reconstructed in Ukraine; a strong call for and praise of industrialisation and workplace competition turned these locations into the heart of the whole USSR: successfully accelerating production and engaging a maximum number of people in shock labour were seen as a clear sign of the triumph of Socialism. Works of the industrial novel genre, aimed primarily to describe life and work at plants and factories, had functioned as a chronicle. It’s indeed possible to get certain evidence when reading such novels but they won’t give a real picture on any given object’s construction or specifics of working there during the implementation of the first or second Five-Year Plan. However, these texts, especially those that were published in large numbers and several editions, added to the creation of mythologemes about a certain factory or region. Thus, reading these novels can give valuable material for researchers interested in how the myth around a factory and a proper (Communist-conscious) working process. Unfortunately, industrial objects and the overall industrial heritage of the USSR rarely appear in the spotlight of researchers and Ukrainian citizens. Ukraine still remains an industrial state whose official narrative encourages investors to launch productions here; a large number of residents have some experience of working on the production or living with such a worker. After all, the issue of labour and its emancipatory potential, touched upon during the first years of the USSR, wasn’t resolved but made its way into the present. Besides, reading this type of literature allows collecting various evidence about the daily routine, rhetorical devices, and communication with the West. This helps to understand the specifics of a superstructure in each given period of time, as well as compare the theory and the political programme with artistic practice. This article suggests comparing two editions of the same novel and discovering what could presence and absence of certain things and ideas mean in the texts with a completely identical subject, characters, conflicts, and location.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

From the very beginning, Soviet literature was tightly connected with the official governmental narrative. Works of fiction acted as a medium between the party’s actions and ideology and the people. In a system of Soviet literature, the industrial novel had a prominent position because, essentially, this genre that started its development along with the first Five-Year Plan, explained to the citizens why it’s important to work, how to do it properly, and what reward everyone who works hard and encourages others will receive. A communist idea is inseparable from the Marxist claim that a person can find fulfilment only through labour. Thus, a path to a free and happy human lies through a worker; the condition is that one should work for themselves and not for a private employer who doesn’t help to unlock their potential but only exploit them and doesn’t give enough resource for growth. The USSR proclaimed to be a country of workers (and peasants), and therefore all the domains had to, at a certain level, address the issue of labour and its value and potential. Besides, it was an agrarian empire that experienced the first attempt to build a Communist world, and for achieving such a goal, it was needed to promptly and decisively industrialise all possible fields of production and geographic points. Calling for industrialisation and demonstrating its importance also played a significant role in the public domain of the early USSR. Finally, the genre of the industrial novel can be seen as the apogee of the urge to show working processes and the need to explain people the processes happening around them.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

The genre of the industrial novel emerged during the first Five-Year Plan and had several functions: 1) it explained the importance of industrialisation and socialist competition; 2) it explained the difference between working for a private employer (a landlord) and the state (working for oneself); 3) it created the chronicles of buildings and reconstructions of plants and factories in the republics of the USSR; 4) it established a new vocabulary which didn’t exist before; 5) it had to explain the readers, in terms of Komsomol members and Communist Party organisers, what is bad and what is good, why bourgeoisie will always be as it is etc.; 6) it entertained. Since there were numerous constructions of new industrial objects during the time of industrialisation, Soviet Ukrainian literature can offer some fiction involving lots of such constructions.

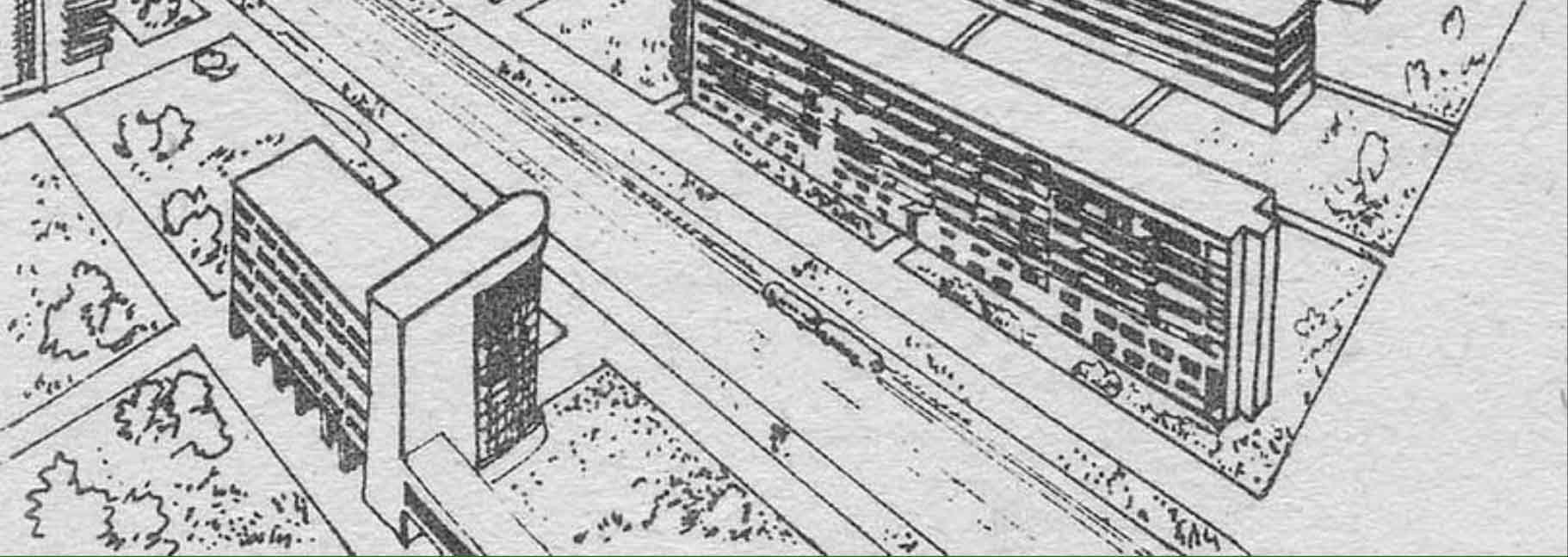

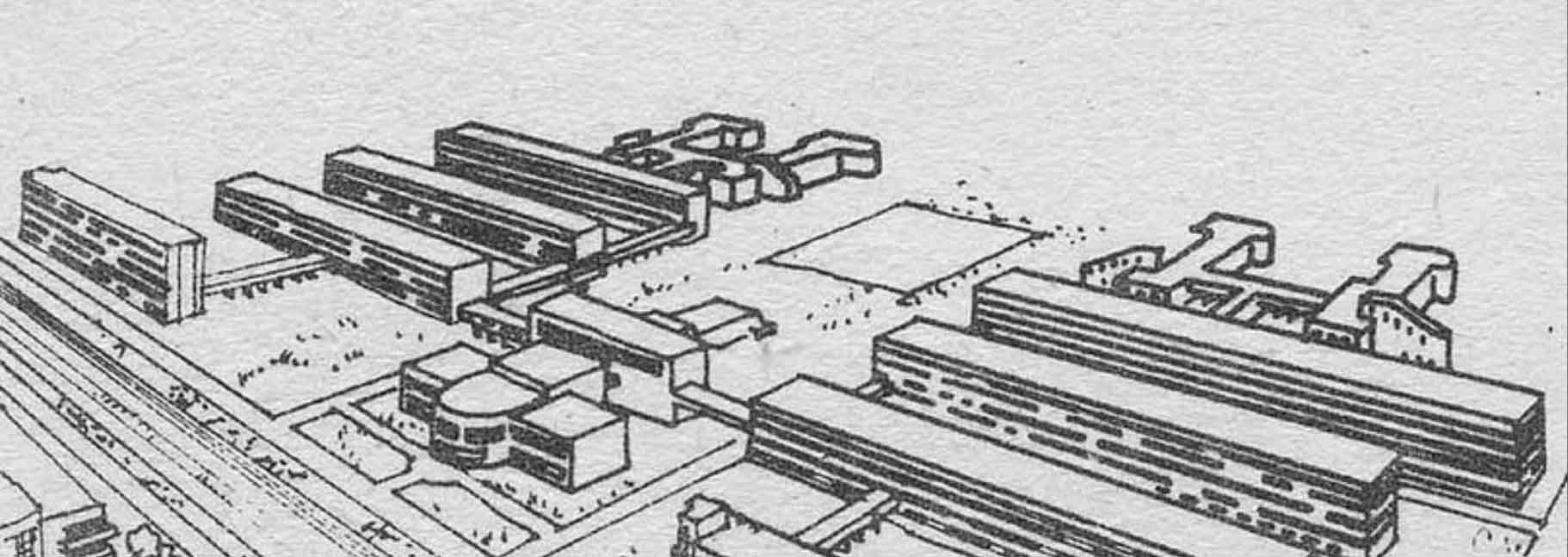

The City is Being Born by Oleksandr Kopylenko is a typical industrial novel written at the beginning of the genre’s development. The story is built around the construction of a residential district near the tractor plant. Although it wasn’t specifically mentioned, readers of all generations knew it was about the buildings for workers of the Kharkiv Tractor Plant. The positive characters of the novel are a chief construction engineer, a section leader, a crew forewoman, a party organiser, a crew of plasterers, while the negative characters are represented by a crew of ‘lazy’ specialists and a family of professors. Such a division of roles is typical for the genre. The main conflict is centred around the protagonists’ willingness to build a residential complex in four years while antagonists want to reduce the effectiveness as much as possible in order to… reduce the effectiveness (it’s not a tautology but their purpose). The fact is that all shock workers put their effort into extending and accelerating construction because they believed that Socialism would emerge after they had finished the Five-Year Plan in four years; they were even referring to it in the present and not the future. The intentional reduction was considered a big crime as it delayed or made impossible the quick arrival of Socialism. The first edition of The City is Being Born was published in 1932, before the official announcement of the literature’s transformation to adopting a method of Social Realism. The second edition came out in 1952, on the wave of renewed interest in ‘classical’ pieces of this genre caused by post-war reconstruction. Knowing the rules of Social Realism, as well as late Stalinism, quite well, the author edited the book himself. Thus, we have one novel and its two editions: the conflict, subject, and characters are the same but the difference between the two is significant. In a broader meaning, it is the difference between the Soviet (biased) art before and after the arrival of Social Realism. Or, we can see two approaches to writing in these editions: before the repression and curtailing of creative autonomy and after the emergence of strict rules whose violation was made punishable.

The two editions also allow following the process of transformation of the official narrative and the way of talking about women, family, foreigners, the figure of a superior, workplace ethics, and views on workers’ routine. In the 1952 edition, construction of a residential district is seen as an important step in building Socialism: having a place to live meant opportunities for improving health and wellbeing for workers, which, in its turn, led to expanding production. Accommodation is depicted in an absolutely pragmatic way, as a warm and clean place for resting after exhausting labour. Within this genre, it was typical to ‘settle’ the characters in places with poor housing conditions and place emphasis on the mess, the lack of heating or water in order to further highlight the level of commitment and stoicism of the Socialist construction heroes. Which is why clean and warm accommodation would often be associated with the victory of Socialism. In the 1952 novel, there’s a scene with a meeting where a phrase that somehow falls out of context is uttered. One of the speakers addresses the need to intensify cost-saving measures in construction and refers to the previous plan of building heated corridors between the buildings. It contradicted a rhetorical situation of the novel which depicted the environment where everything was untidy, old, and reduced to the minimum and women were going to work barefoot. The idea of heated corridors which would connect different buildings was odd and illogical. But the first edition of the novel gives an explanation: at that meeting, a speaker was not only addressing the need to accelerate production and economise but also expressing a popular and ideologically correct opinion on a socialist city of that time:

Besides, according to the project, all buildings of each housing complex should be connected with roofed bright corridors. These corridors cost two and a half million karbovanets for each complex.

‘I don’t understand: what for? Surely, it’s great that working mothers will be able to come to a nursery through heated corridors and residents will visit each other or go to a diner, or a club, or a movie theatre without coming outside. But this amenity will cost us too much… And… excuse me for saying this, but we aren’t much of noblemen and we aren’t that weak to avoid going through the sidewalk to a nursery or a club once more… We are building a Socialist city, a city of a new collectivist and collectivised life. Everything in this city will exist for comprehensively serving the residents. Including nourishment. Factory kitchens will cook food while factory bakeries will make bread. We can always have warm meals in diners and buffets. What for, then, do we have to put a heater in each room? Just calculate how much money these heaters themselves will take… By my count, the state can save over three million karbovanets on each housing complex, with ten buildings each. In a year and a half, it’s fifteen million karbovanets on the first five complexes. Comrades, think how much this cost-saving brings us closer to Socialism’.[1]

Since the second edition came out during post-war reconstruction, cost-saving was seen not as an opportunity to drastically expedite the victory of Socialism but as an important production rationalisation. Besides, the second edition was based on other ideological principles which discarded any idea to free women from household chores, while in the first edition, female characters would often talk about the death of the family institution and how they hated the ‘stove.’ As we can see, the abandonment of the heated corridors idea was seen as a compromise on the great goal of full emancipation for the sake of expediting Socialism during the first Five-Year Plan while at the time of the second edition, it was seen as a criticism of profligate spending and the desire to improve living conditions.

The novel provides one more extensive description of the ideal Socialist city of the future. Its second edition depicted a world where there were lots of green spaces between the buildings and the factory: it was even claimed that “plants are the best air filter.”[2] Also, the infrastructure of the residential district allowed receiving various services on-site. In this regard, the first edition isn’t much different but it tells about collectivising household affairs: there was a plan, later abandoned, to reorganise citizens’ private lives:

All the household goods are collectivised in Stalgorod [Steel City]. Please note that it won’t be collectivised but already is: the first buildings constructed by these workers don’t have kitchens or laundry rooms. There’ll be no need to care about food, children, or laundry. When a worker comes back from work, they have a library and a gym, a park and a science lab at their disposal.[3]

It’s obvious that rejecting the need for a private household (owning a kitchen and a laundry place), the first edition meant not only the elimination of such rooms in apartments but the abolishment of the need for women to take on extra burdens apart from their main job. In the first edition, characters negatively portray marriage associating it with women's lack of freedom, a bourgeois invention, and inequality. The second edition abandons such radical ideas and tries to very carefully erase them from the text. At the same time, the main purpose of a woman in this country during post-war reconstruction was still associated with their construction or production jobs. Both editions depict a pregnant cook who returns to work right after giving birth and keeps a child in a suitcase under the countertop. The difference is that in the first edition, everybody admires such attitude and sees a strong dedication to work and faith in the victory of Socialism in the cook’s decision, as well as a radical liberation from household affairs and conventional ideas about women’s role. In the second edition, there are no thoughts on such radical liberation and no great affection to such a determination to return to work.

Soviet literature critics demanded from writers to pay attention to class conflict within each piece of fiction. They often criticised writers for their inability to plausibly depict or fully understand this conflict and means of expressing it. The first edition of The City is Being Born was created when there were no standardised scenes for demonstrating class conflict, which is why the early pieces of the genre of the industrial novel include some unusual examples of demonstrating the viciousness of the bourgeoisie and their intrinsic hostility not only to the idea of Communism but also to regular people (proletarians). One of the female protagonists came from an educated family that had a privileged position under the former regime and managed to save their possessions and occupations under the new regime. However, all family members except for this character felt nostalgic and suffered from the pain of losing their social capital: since a new country had proclaimed that everyone was equal, no one would bow to or fear either professor or his son who occupied a high position in a trust. Even though the novel tells about a worker, the lack of respect to workers, according to Marxist ethics, means the lack of respect to people as such; and this pain of loss and intrinsic disrespect to people are revealed through the deceleration of production intended by the trust's authorities and also through parodying and ridiculing workers and their habits. There’s a striking difference between the two editions in what this female character’s brother says in his monologue. In the first version, he criticised the party’s urge to build a nice home for workers:

‘Listen, are you done with that famous building that should embody all the Socialism? A very interesting building. I should explain to those who don’t know. According to the project, it looks like this: a working-class person enters a big vestibule decorated with palm trees, flowers, and other elements. There are upholstered furniture and small tables. Shock worker Van’ka Zub comes to visit his friend to talk about Socialism. But another shock worker Kostia Zadripa unannouncedly stabbed his friend under the ribs because of having lost his girl, Man’ka, to him, solving in such a way the problem of a new state of life. There’s no need to run far away for medical care. Right there, in that very same vestibule, there’s a door to a doctor’s office who can apply a bandage. Then, our hero Van’ka goes up the wide stairs to have lunch in a Socialist diner. He sits at the table in this workers' co-operative hashery and eats his Socialist grub which causes such nausea in his weather-beaten flesh that he runs away on the balcony. The balcony goes along the whole floor and that’s where Van’ka quickly pukes and curses those who regaled him with such a meal. Now, this poor advanced group worker wants to buy something for himself. He goes right from the diner, crossing the carpeted stairs, spits on them, of course, wipes his feet on them, and enters a perfectly equipped shop where there is hardly anything you can’t find: you can’t find soaps, bread, sausage, cigarettes, sugar, or even buttons there. But still, with his shock-worker certificate, our hero buys a whole toothpowder box and returns home feeling satisfied and looking enthusiastic. How’s that for Socialism?’[4]

In the second edition, this monologue was cut down:

Giggling spitefully and cynically, Vsevolod began his speech on the workers’ cultural club in a new city. It will be a greatly constructed and equipped building. There even will be a stage so that theatres can put on plays. There surely will be parquet flooring, chandeliers, velvet and silk draperies, expensive furniture...‘Who is this all for?’ Vsevolod suddenly shouted. He even jumped from his seat and went ahead acting out a scene of how would workers behave in their cultural club...[5]

These excerpts are illustrative of the changes that have taken place not only in imagology but also in the author’s autonomy and freedom to depict a real object of criticism and class struggle. At the beginning of the 1930s, bourgeoisie laughed at the idea of giving regular people upholstered furniture and shops in the building, while the image of the bourgeoisie after the Second World War made them laugh at the idea of giving workers a theatre. On the one hand, the ‘enemy’ ‘grew mellow,’ but on the other hand, it was simply impossible to spread the jokes of workers’ enemies – about the lack of basic commodities in shops being evidence of the victory of Socialism – after the 1930s.

German experts, employed under contract, played a significant role in the first edition. They work at the construction site and learn about the new country and the new Soviet human. Kopylenko created two different characters: one German is sympathetic to Communism and therefore asks a lot of questions and retransmits ideas to his colleague who, for his part, rejects any thoughts on the success of this project and constantly emphasises that building Socialism and conversations surrounding this process don’t define the reality; he thinks that a thirst for commodities is the major characteristic of life in the Soviet Union. The first edition gives a German character, as well as others, the place to express their thoughts on the significance of clothes, shoes, and furniture in a worker’s life. The second edition tells nothing about characters’ relationships to material things and doesn’t include any foreign expert. In 1952, there was no need to explain this intensively about a Socialist country, Socialist competition, and the importance of labour.

Both editions of Oleksandr Kopylenko’s novel The City is Being Born are illustrative of the genre of the industrial novel. They tell the same stories and share a lot of the same dialogues and descriptive passages. However, only the second version is a piece of Socialist art; and by comparing the two of them, we can understand how after the proclamation of Socialist Realism, art ‘forgets’ and abandons ideas that were relevant in the early USSR. It happened not because those ideas had been implemented or discredited as unhelpful or unnecessary for the victory of Communism but only because the official party line had edited some discursive political practices. Apart from that, as the industrial novel, The City is Being Born allows following the process of making a myth of the industrial object.

We shouldn’t rely upon the literature of this genre as a chronicle: it isn’t historical fiction and it always fits a certain purpose defined by the party. The inability to understand how to interpret the characters, their emotions and actions becomes a separate issue: current realities don’t give the experience needed for reading these texts the way the author wished and the first readers did. From the perspective of a modern Ukrainian, it’s hard to understand if the first readers felt class hatred towards the antagonists, how much they sympathised the protagonists and worried over the execution of a plan. Also, the book doesn’t provide for understanding if there was some emotional connection between the first readers and the characters. Nevertheless, the two editions of the novel allow learning how the narratives were changed within the official USSR policy.

[1] Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1935. The City Is Being Born (7th Edition), Kharkiv, Derzhlitvydav, pp. 84-85.

[2] Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1956. The City Is Being Born, Kyiv, Derzhlitvydav, p. 179.

[3] Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1935. The City Is Being Born (7th Edition), Kharkiv, Derzhlitvydav, p. 208.

[4] ibidem, pp. 58-59.

[5] Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1956. The City Is Being Born, Kyiv, Derzhlitvydav, pp. 55-56.

-

References

Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1935. The City Is Being Born (7th Edition), Kharkiv, Derzhlitvydav, 2015 p.

Oleksandr Kopylenko, 1956. The City Is Being Born, Kyiv, Derzhlitvydav, 204 p.

Image: Scheme of a social housing estate HTZ, Kharkiv. Photo from the website: http://the-past.inf.ua/list-3-3-8.html

–

Mariia Tkachenko is a literary researcher and post-graduate student at the Institute of Literature of the NAS of Ukraine.

–