What emerges from the air, what dissolves in it

30 October 2020 • Pavel Khailo

A lack of arts infrastructure and a constant demand for its development, along with the dissatisfaction in existing opportunities structure Ukrainian art field. Starting from the 1990s, when a part of creative workers who associated their practices with contemporary art got exhibit opportunities, there’s been a hope hanging thick in the air for the museum of contemporary art to emerge near a supermarket, bank, and PR agency. And still, there’s the same frustration coming from the fact that every new ‘institution’ turns out to be not a part of the art field but rather a supermarket, bank, or PR agency (or most often a bit of each).

The first issue of the Ukrainian contemporary art magazine Terra Incognita (1994) is dedicated to this hope and anticipation of a museum. In the first sentence of the opening article, Glib Vysheslavsky states that “there almost aren’t institutions in Ukraine that would support new contemporary art tendencies” [1]. 25 years after, artist, curator, and teacher Lada Nakonechna documents a similar situation in the article The Unclear Institutional: “organizations that position themselves as new contemporary cultural institutions in Ukraine are mostly distributing and popularizing art, while we clearly lack those that would contribute to its creation” [2].

In 2020, there’s still no such museum that was so much anticipated in 1994, even though it has many times created news and rumors about its establishment in Ukrainian House, the President’s Office on Bankova street, and an unknown building next to Livoberezhna metro station. Announcements about this always non-existing museum moving places are symptomatic for institutional processes in general. While solids dissolve into the air, contemporary art organizations and initiatives active in Ukraine are created from the air. Cloudy, non-transparent, and always fluctuant, they can somehow survive. They function as air castles that we build, “forced to address the philanthropy of bourgeois hearts and wallets.”

Analyzing the context of the 1990s, director and writer Oleksii Radynskyi claims the following: “the development of contemporary art infrastructure is a part of the liberalization process of post-Soviet economics. Art was declared to be an institution of a liberal society, same as transparent election, while artists had to become somewhat like electoral committee members” [3]. However, as we follow Radynsky’s metaphor, artists have later lost — without having properly gained it — the role of official monitors and have become volunteers, moved even further away from the chance to have a real impact. Now, creative workers are more often perceived as content producers, applicants to programs and open calls (with participation in those perceived as a definite acceptance of game rules), or temp workers with a fee that seemingly makes it impossible to have the right not to agree with the politics of an exhibition venue, fund, or other organization.

Nevertheless, artistic and activist strategies of the arts infrastructure critique are still there, emerging from the imaginary space where such activity can have structural consequences. Similar anticipations often come from artists (rightfully) feeling to be a part of the history of global institutional critique. However, the venues their critique is directed at are not part of this history and in many ways remain basically ahistorical. “We don’t have our institutional system being built as we have it being imagined” [4], states philosopher and art historian Boris Kliushnykov while describing a general framework of critical interaction with the arts infrastructure in Soviet and post-Soviet contexts.

Such interaction with the imaginary has paradoxical consequences as in its negativity, it fixates the forms of arts infrastructural objects for some moment, which allows talking about them somewhat determinately. Although, there’s an opposite side to it: such artworks get lost and disappear from the memory due to a lack of archival organizations. The purpose of this text is to reveal these strategies, at least partially. Article limitations won’t allow me to fully systematize and describe all artworks created after 1991, and some of them may be totally unknown to me, again, due to a lack of archives. I didn’t include escapist anti-institutional strategies that proposed to completely ignore the existing infrastructure. Also, I didn’t include a whole range of works and initiatives that emerged as a critical reaction to the educational system in Ukraine. This critique deserves a separate study. Strategies covered in this text are not organized in a certain order to represent a linear development process. Instead, I try to reveal controversies in different strategies, often based on political or aesthetical standpoints opposite to each other.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

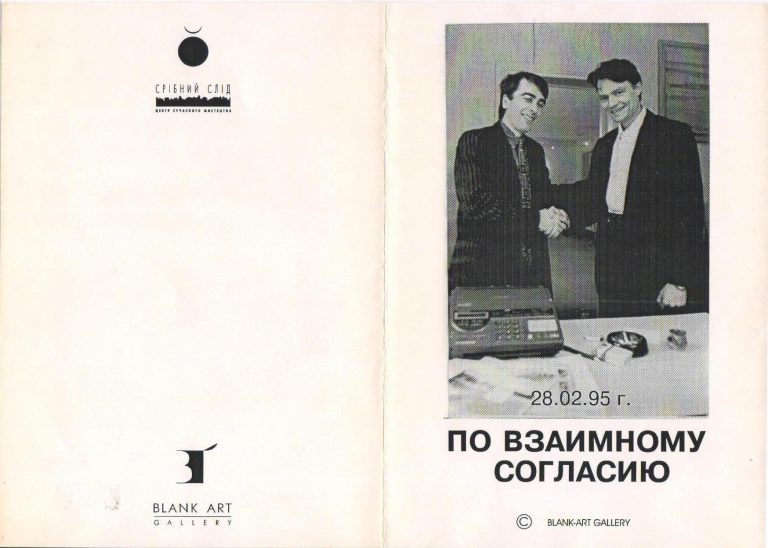

Vasyl Tsagolov, Oleksandr Blank. Invitation to the performance By Mutual Agreement, 1995. Source

1. Mimicry and interception of functions

The action exhibit by the Quick Response Group (Bratkov, Mykhailov, Solonsky) called Sistine Madonna was one of the first practices of critically approaching art organizations in Ukraine. It was held in 1995 in the Up/Down gallery, a self-organized venue in Serhii Bratkov’s own studio in Kharkiv. He described the situation as follows: “There was a Salvador Dali exhibition and then Pre-Raphaelites one where only reproductions were exhibited. Obviously, we were outraged: how’s that the museum only shows reproductions? We tore up the book with Rafael’s works, hung them up in our studio, and demanded the same entrance fee as the museum had'' [5]. Copying the museum’s politics in a hyperbolized manner together with placing an artwork in a specific place allows us to analyze the problem without having to deal with the organization itself and act from a safe distance. Moving an artwork to a self-organized venue makes organization and management more complicated: criticism towards the museum’s attempts to adapt to new market rules is placed in a scanty space of a studio that has itself emerged to meet the infrastructure demands. At the same time, the Quick Response Group wasn’t that much alienated from the traditional museum and didn’t take it exclusively as a symbol of conservatism. Artists did try to cooperate with it, but in 1994, the museum director shut down Boris Mikhailov’s exhibition Before and After America/New Photographic Expressionism (also featuring Serhii Bratkov and Serhii Solonsky).

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

Masoch Fund, Time of Sponsors, 2004, part of the brochure. Source

2. Reacting to censorship

Institutional processes resulted from censorship by exhibition venues spurred some of the most notable and continuous discussions. I’m talking about the ruining and closing of the New History exhibition curated by SOSka in the Kharkiv Art Museum in 2009 and the destruction of Volodymyr Kyznetsov’s work Koliyivshchyna. Judgement Day in 2013.

The New History exhibition had to create a space for dialogue, putting classical works and works by contemporary artists against each other. The museum itself and its operation weren’t in the focus, however, were brought to light because of the act of censorship. The exhibition was shut down and museum director Valentyna Myzgina personally destroyed the artwork by David Ter-Oganyan. As a result, curators shifted their focus on discussing the very fact of this censorship with the museum director acting as its only owner. “It was her personal decision motivated by the thought that she practically owned the museum and that was the territory she could do anything she wanted to, according to her personal will. It flatly contradicted the notion of a museum as a public space” [6].

The situation with Volodymyr Kuznetsov’s artwork being painted over right before the Grand and Great opening is structurally similar. Censorship was also initiated by the venue’s director. But in this case, it wasn’t a traditional museum not closely incorporated into the contemporary art infrastructure but the largest government-backed venue focused mainly on contemporary art. This censorship provoked a reaction out of critically-minded artists and led to a strike, which isn’t over in 2020. The trial initiated to admit censorship is also still ongoing. I should add that in these 7 years, Mystetskyi Arsenal made some concessions, for example, the act of censorship was partially acknowledged (“...from the professional and ethical perspective, it was a creative censorship” [7]) and some changes were made regarding artist fees.

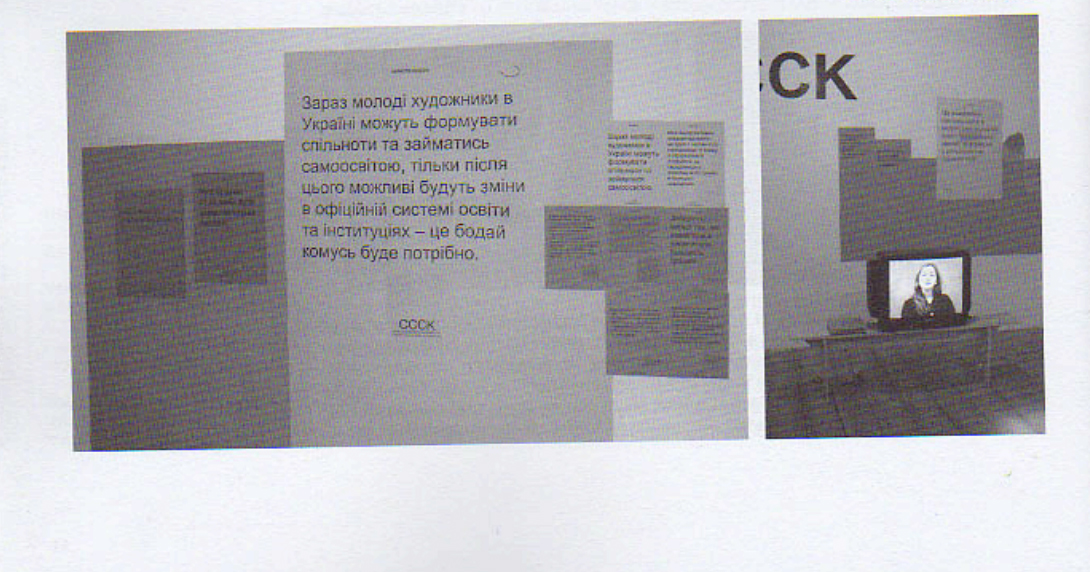

Part of the CCCK publication that documents the Postfunding project in the Vector magazine. Source

3. Attacks and interventions

Another strategy incongruent to organizers is intervening in or attacking the event or organization. Combine of Ukraine (1993-1997) artists (Petro Mamych, Igor Ishchenko, Volodymyr Zadyraka, Pavlo Shydlovsky, Serhii Lukashov) were pioneering this approach in Ukraine. Being pro-anarchists, they aimed to make contemporary art the practice of the masses. Their manifesto says, “Artists themselves would destroy the reactionary myth about artists being the chosen” [8]. They put theory to practice in contractions: “The point was to intervene in the artistic and social space already structured by other artists” [9]. They pursued a goal of doing “moral damage to a champion” [10] as a symbol of success and therefore elitism in art. Contractions that took place at Kyrylo Protsenko’s exhibitions (1995) and attempts to attack Vasyl Tsagolov’s project Masepa (1995) are notable examples of this strategy. The possibility of a direct critique happening in the moment of exhibition opening disrupted old conventions and turned the art community space into a space for discussion. And the very logic of aggression was also subject to reflection: the group exhibition called Aggression held in 1996 in the Blank Art gallery included a series of discussions about such strategies in art.

Later, the Unnamed group consisting of 10-15 members applied similar strategies while attacking the Revolution. Suprematism. Maidan exhibition in 2015. Interestingly, the intervention started before the event itself: enthusiasts created social media accounts for avant-garde artists and wrote posts in the Facebook event discussion from their names — and eventually were blocked by organizers. There was even an alternative event page that almost entirely copied the original one. Organizers were making excuses but dodged all critical questions. Members of the Unnamed group came to the opening masked as avant-garde artists and entertained everybody with vodka.

Among the works relying on a potential scandal, naturally, there were some created for personal advantage. In 2000, the New Creative Union that included Arsen Savadov, Olga Malentii, Valentyn Raievsky, and Oleg Tistol set up the action called Tasteless Art: they threw a cake in the face of the Contemporary Art Centre curator Ezhi Onukh at Pavlo Makov’s exhibition. This event was a part of a scandalous conflict between artists and Onukh for the right to represent Ukraine at the Venice Biennale for the first time. Besides this public attack, the group issued an appeal to the minister of culture, asking to remove another country’s citizen from the post of curator and follow the formal rules of the selection process. I should note that there was indeed a lack of transparency in Onukh being assigned to curate the Ukrainian pavilion by Yevhen Karas, and it was used as a valid argument in the conflict. We should see this example as a characteristic of the system where the demand for following the rules might hide the wish to get the resources.

In his performance Disable (2012), Petro Armianovsky tries to visit PinchukArtCentre as a disabled person. In this case, the exhibition visit itself becomes the intervention that assesses how accessible the space that declares its accessibility actually is. This performance demonstrates how the centre’s architecture and exposition impact the way people can interact with art and also reveals the low staff's commitment to ensure actual accessibility.

Valentyna Petrova’s work YES or NO (2019) is a notable example of coordinated intervention. Executed as a quest game, this work was performed during the exhibition A Space of One’s Own in PinchukArtCentre. It turned the whole exhibition into a critical statement against itself, acting as an alternative curation attempt. Valentyna accentuates the political component of each work and the problematics of their presence in the exhibition space, revealing how those are connected to the venue’s economical logic and its dependence on the oligarchical capital. The non-material nature of the work and its short duration (the game was available for one day) allowed the centre to incorporate direct statements which it usually avoids.

Lada Nakonechna, Exhibition, 2016. Source

4. Processes become a form

Another interesting strategy is to use interaction with an organization as a material for work. Video Office Games (1998) made by Myroslav Kulchytsky and Vadym Chekorsky is one of the examples here. By its form, it looks like absurdist poetry: phrases taken out of conversation appear and disappear in the video. From its explication, viewers learn that all the phrases are fragments from conversations that took place in the Odesa centre of contemporary art. There are everyday jokes, senseless comments, and friendly (or not) invectives instead of discussions about art. People involved in these conversations are narrowly known and odd to the wider world, as well as the centre itself, at least in its stereotypical image. In addition to that, in these conversations, people indicate the office-like status of the centre and focus on the routine nature of their work and its structural similarity to any other domain.

Lada Nakonechna’s Exhibition (2016) created in PinchukArtCentre is one more example of the abovementioned strategy. The exhibition space became the exhibited item: correspondence with the administration about the event was shown among other objects. However, Exhibition doesn’t that much accentuate its documental nature as it casts doubt on institutional transparency, making the centre’s space more complicated and the walls less neutral. A peep hole in the wall that allows seeing other spaces through it is an important exposition detail. It’s more of a way viewers see and not what they see. “Transparency per se is no longer an exclusive responsibility of people in authority but quite the opposite, it motivates other participants to claim their rights and join the dialogue” [11], writes Anna Smolak in supporting text to the exhibition.

The Mediators group showed an activist approach to work in Application Form (2018). Two group applications to the PinchukArtCentre prize (from 2015 and 2018) became an artwork. Both times mediators applied to the prize, they didn’t make the cut. Their proposals are a part of their fight for labour rights in the centre and the attempt to gain the space for expression at the same place where their rights have been systematically ignored.

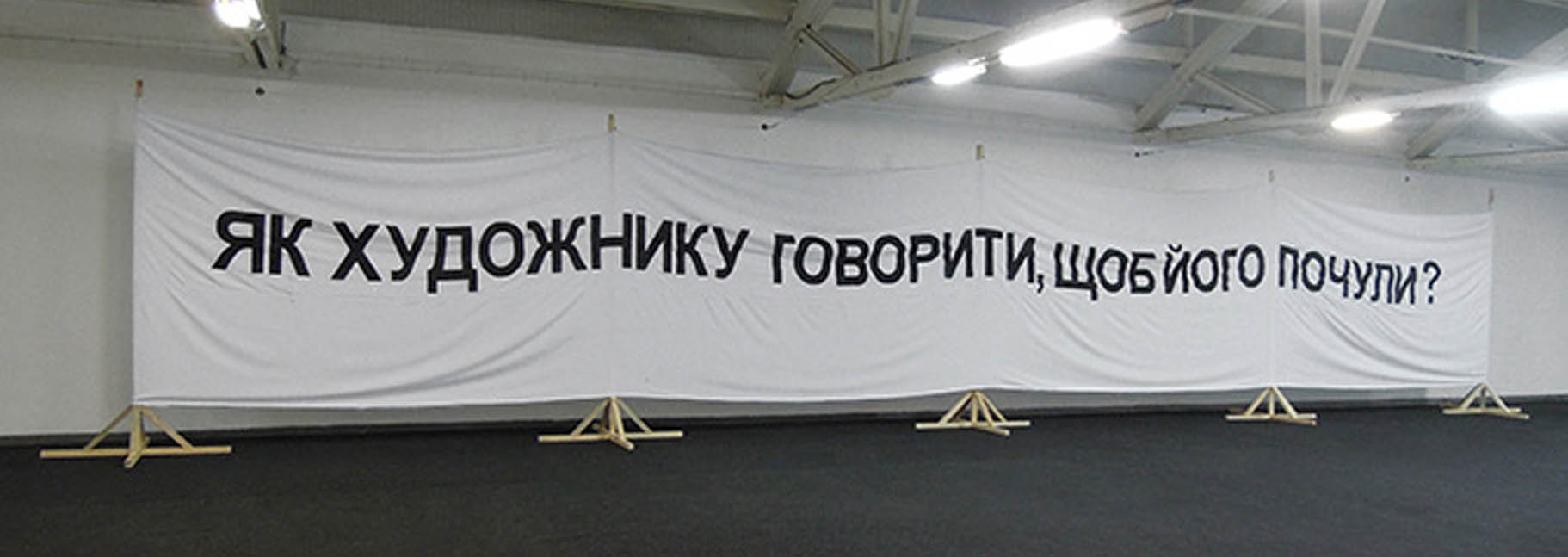

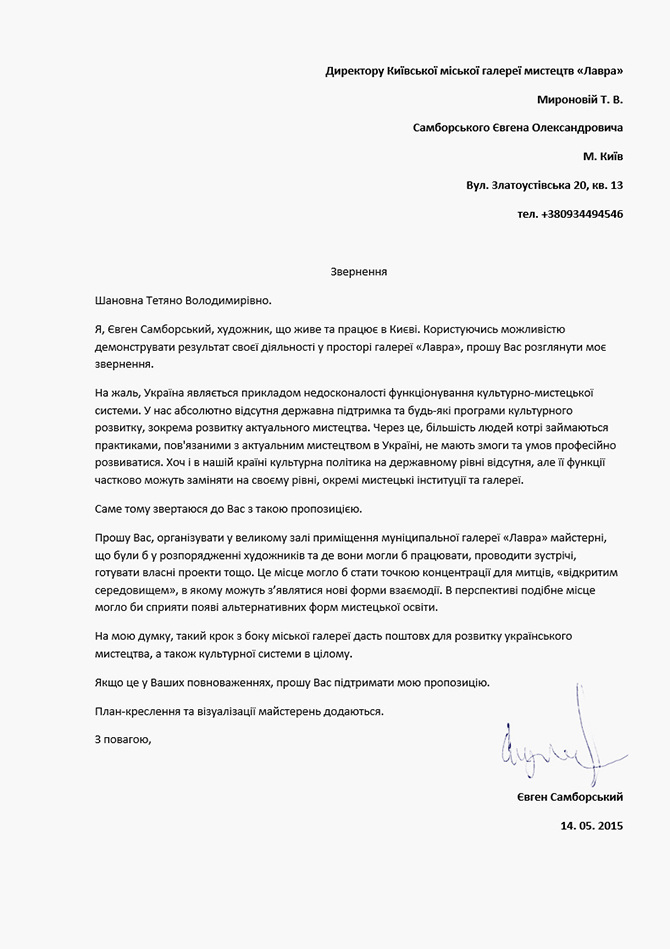

Yevhen Samborsky. Questions. Attempt of a Dialogue. More of Something Important. Created for the Kyiv gallery Lavra, 2015. Source

5. Additional topics for revealing history

The Big Surprise exhibition held in the National Museum of Arts in 2010 sponsored by the Renat Ahmetov’s fund technically was dedicated to giving the spotlight to tuberculosis. The R.E.P. group, however, approached the museum space and not the exhibition’s theme. Instead of displaying new artworks, they tore down false walls and brought back to light that part of the display that was sidelined by the museum — socialist realist works in particular. Copper signs placed in different parts of museum halls that had colloquial language rather than academic text on them also became part of the exhibition. With that said, the R.E.P. group introduced a structural approach instead of just illustrating the problem of tuberculosis’ invisibility. Operational intrusion and adding one more dimension to the exhibition allowed for complicating the museum's display.

In Beetroot Revolution (2018), Larion Lozovy also incorporates other themes to level critique at arts infrastructure. Designed based on the late-Soviet museum canon, it features a didactic voiceover telling about the connection between avant-garde artists of the beginning of the 20th century and the capital of sugar mogul Mykhailo Tereshchenko. In the context of the PinchukArtCentre Prize for young artists, this work was an obvious hint on how the centre’s sponsor instrumentalized artists’ expressions. Even though it doesn’t pass direct judgment on the centre or its owner, it still shows that art is systematically dependent on someone’s capital.

Larion Lozovy, Beetroot Revolution, 2018. Source

6. Cooperation

In the 1990s, the Blank Art gallery was among the first private exhibition venues open to experiments. In 1995, artist Vasyl Tsagolov and gallerist Oleksandr Blank initiated the performance called By Mutual Agreement to raise the issue of how the power is being distributed inside the art system. It looked like a formalized signing ceremony with public disclosure. But it was only the beginning of the performance: Vasyl Tsagolov took on the role of a curator aiming to “end up the gallery’s operation” [12]. “The goal Vasyl Tsagolov (the Artist) pursued was to become an ideal mechanism of Power, a naked function of misdoing of any kind of norms, values, and meanings the structure of power relies upon” [13]. In his turn, Oleksandr Blank was vocal about his intention to stand in Tsagolov’s way: “The essence of the future series of experiments is applying all the variety of repressive means of Power that are already a mundane norm of a modern society to the Artist, Vasyl Tsagolov” [14]. From his part, Tsagolov called himself a curator but the gallerist referred to him exclusively as the artist and by doing so, he pushed him out from the actual impact on the gallery’s operation. The idea was further developed in a game-like manner and embodied in conventional art forms. But the logic of raising the issue of power through cooperation demonstrates the new to the Ukrainian context situation where an exhibition venue can benefit from the critique.

In 2006, the Open Society Foundation started scaling back the funding given to centres of contemporary art in Eastern Europe. At that time, the project called Centre of Communication and Context was initiated by Ingela Johansson, Volodymyr Kuznetsov, and Inga Zimprich. They focused on the influence Western capital had on the new art establishment in the region and the situation after the funding. The project included an exhibition, a series of discussions, and publications that studied how different centres of contemporary art in Kyiv, Odesa, and other cities functioned. It was one of the first examples of Western institutional critique in Ukraine supported by a Western institution. The very international collaboration was enabled because of the Centre. It’s symptomatic that in 2020, searching for the information about this project online, one can find English-speaking resources, while there are no Ukrainian websites able to keep and support public access to research materials.

Questions, Attempt of a Dialogue, and More of Something Important (2015) is Yevhen Samborsky’s attempt to impact the practices of the municipal Kyiv gallery Lavra. This work was divided into three parts, with the second one — Attempt of a Dialogue — being an attempt to change the way the exhibition venue functions through a dialogue with management. In his official letter, artist proposes to turn the gallery into studios given that creative workers have bigger problems with opportunities to create art than exhibit it. This proposal didn't lead to any actions by management and remained a part of the exhibition’s documentation.

Documentation of the Suprematist Play action by the Unnamed group. One Can Not Be Too Careful exhibition, Minsk, 2017. Source

7. A forced gift

Another strategy, the most complex and interesting one, is about a gift as a chance to reveal the problems of arts infrastructure. It’s especially actual when organizations are focused on forming collections and therefore are interested in receiving new artworks. In 2004, Masoch Fund (the group of artists Ihor Durich and Ihor Podolchak) held an auction called Time of Sponsors where they were selling personal belongings and artworks of fellow artists, writers, and other famous people. The funds were intended to be put to procure contemporary art for the collection of the National Museum of Art in Ukraine. Artists aimed to reveal the very logic of such procurement given that the museum's collection hadn't been renewed since the 1990s.

They even created a fictitious organization called the Institute of Actual Culture, although the event preparation was not very well thought, which signalled it being a single action rather than systematic work. As a result, the auction failed and didn't catch much investor interest. Some artworks, however, did find their way to the National Museum and triggered systematic changes there. As art historian, curator, and researcher Oksana Barshynova claims [15], it's largely because of this auction that the museum has gained a contemporary art department and established practices of storing and registering artworks made using non-traditional techniques.

Another example of this approach can be seen in the work by R.E.P. called Column for a Museum. In 2011, the group donated a kitsch plaster slab construction that masked an unrestored column in the exposition to Mystetskyi Arsenal. This work continued a theme of a European-style remodelling the group had been focused on. The switch in representation moved from the problems of the institution to its structural processes. The work started functioning not only as a temporary object in the exposition but also as a part of the organization and its problematic property. And the moment of giving the artwork to the institution drives even more attention to it, while making it into the collection continues the artwork's life cycle despite the institution’s wish to ignore and forget about it.

[1] Glib Vysheslavsky. Reality and/or Knowledge. Introduction to Terra Incognita. [Гліб Вишеславський. Реальність та/або пізнання. Вступ до часопису Terra Incognita] // Terra Incognita, №1, p. 3.

[2] Lada Nakonechna. Institutional Made Unclear. Part 1 [Лада Наконечна. Інституційне непрояснене. Частина 1.]

[3] Oleksii Radynskky. Contemporaryart. [Олексій Радинський. Контемпораріарт.]

[4] Boris Kliushnikov. Institutes and Self-Organization Imagination. [Борис Клюшников. Институты и воображение самоорганизации.]

[5] Mikhail Sidlin. The Art of Brutal Irony. [Михаил Сидлин. Искусство брутальной иронии.]

[6] Discussion. How Many Contemporary Art Practices for Museum Ruins? [Дискусія «Скільки практик сучасного мистецтва для руїн музею?».]

[7] 2017 report by Mystetskyi Arsenal [Річний звіт Мистецького арсеналу за 2017 рік], p. 15.

[8] Apology. [Апологія]. Kyiv, 1996, p. 6.

[9] Glib Vysheslavsky. Art Processes in Ukrainian Contemporary Art of the 1990s. [Гліб Вишеславський. Художні процеси у сучасному мистецтві України 1990-х рр.], 2008, p. 60.

[10] Kaliban (self-published). [Самвидав Калібан], №1, 1996.

[11] Anna Smolak. Supporting text for Lada Nakonechna’s ‘виставка/exhibition.’ [Анна Смолак. Текст до виставки Лади Наконечної «виставка/exhibition».]

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Discussion. Theorizing the Ruins. Institutional Archives. [Дискусія «Теоретизуючі руїни. Інституційні архіви».] NAMU, Kyiv, 2019.

–

Header photo: Yevhen Samborsky. Questions. Attempt of a Dialogue. More of Something Important. Created for the Kyiv gallery Lavra, 2015. Source

–

The article is published under the Course of Art program Positions of an Artist, supported by the Ukrainian Cultural Fund.

–

Pavel Khailo is an artist and researcher. Lives in Kyiv.

–