White Gold (No Man is an Island)

25 October 2019 • Larion Lozovoy

This text is a continuation of my interest in economic history of Central and Eastern Europe, particularly a period of industrial and cultural elevation that the Russian Empire owed to its "agrarian powerhouse" – sugar beet. Unlike previous attempts[1], I wanted to look at the effects of this commodity on a global historical scale. Being one of the first goods produced in various parts of the world, it helped formulate the concepts of the global market and free trade – in the way we know them. In turn, competitive philanthropy became an integral part of the ideology of entrepreneurial success, heralded by the new class of industrial bourgeoisie. Its side effect – an interplay of selflessness and mercantilism, and growing mutual dependence between cultural producers and magnates of the industry.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

“White Gold”

THIS IS A SAMPLE HEADING STYLE 1

Sugar beet, the agricultural powerhouse of its era. Hidden deep in the soil, it absorbs solar energy and accumulates carbohydrates at the rate unmatched by any other plant cultivated by humankind. Its influence extends far beyond agriculture. Ever since its discovery, this unprepossessing root vegetable has been sealing the fates of states and potentates, colonies and metropolises, the old order and the new. Wherever it is cultivated, cultural evolution spreads. Those who control the resource can undermine current orders and enforce their own.

The remarkable history of our protagonist goes back to the 16th century, when European alchemists began to experiment with beetroot and its sugar-bearing properties. These experiments accelerated when alchemy transmogrified into modern scientific practices. In 1747, the Berlin-based professor Andreas Marggraf, an early modern chemist, extracted sweet crystalline substance from beet. Although its gustatory properties were no worse than those of cane sugar, Marggraf did not see the practical implications of his discovery. And yet, his student Franz Achard developed a new beet breed with increased sugar content, and established the first sugar refinery in Europe in Silesia. The root was implicated in global politics since its early days. During the Napoleonic Wars, France found importing cane sugar from its colonies increasingly hard due to the naval blockade enforced by the British navy. The price of the product that the public had grown accustomed to soared. Righteous indignation over the fact that sweets might become the privilege of the wealthy yet again made the masses take to the Parisian streets. Subsequently Napoleon decided to produce sugar in France, and invested millions francs into the development of the national sugar industry, which soon flourished. France did not only overcome the “white gold” shortage, but was also ready to sell sweets to neighboring markets.

The news of the success spread across the continent. Not ten years later the government of the Russian Empire started adopting decrees on cultivating the national sugar beet industry. Central Ukraine, with its mild climate and suitable soil, would become the center of the new agrarian power. The success of the first refinery founded in Makoshyn ushered in a veritable beet mania that swept across the districts along the Dnieper. After the peasant reform of 1761, a new class of agrarian industrialists emerged: having bought up the land from bankrupted gentry, they entered stiff competition in “white gold” production. Eventually they would prioritize uniting their efforts rather than competition: the refiners of the first wave joined forces against the new players seduced by the prospect of staggering profits associated with sugar-beet fields.

This led to the establishment of the Russian Sugar Producers Society, a syndicate uniting the empire’s largest producers. Ukrainian magnate families, including Bobrynskyi, Tereshchenko, Kharytonenko and Brodskyi clans, played the leading role. Its headquarters were in Kyiv, the new “sugar capital.” The sugar business soon became a monopoly, with most of the sugar industry amassed in the hands of the 5 largest families. They led the national sugar industry from one victory to the next, becoming household names in Europe and setting the rules in the closest foreign markets. The czarist government acknowledged the refiners as the rising power. Seeing the direct correlation between the national budget and sugar excise duties, the czar granted refiners titles and ministerial positions. This allowed the magnates to dictate the state’s economic policies, openly or covertly. Therefore, the white root vegetable absorbing sunshine in the wooded steppes of Ukraine was more than a source of carbohydrates. The control over the “sugar beet belt” promised substantial power to the lucky few contenders.

In commodo lectus imperdiet, convallis est ut, efficitur nisi. Nulla scelerisque sollicitudin aliquam. Vestibulum rutrum lacus et convallis molestie. Nam dictum erat purus. Duis consequat elementum congue. Cras metus tellus, rutrum eget lorem a, posuere tristique nunc. Donec tincidunt ante at ligula aliquet blandit. Ut volutpat mi et ex tristique, a porttitor ante fringilla. Quisque feugiat turpis nec lorem mollis dictum. Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

Leon Wyczółkowski, Beet Harvest I, 1893

Image caption: Integer vulputate libero quis neque pharetra, pretium viverra ex euismod.

Granted, the staggering success of the Ukrainian sugar beet industry was underpinned not only by fertile

soils but also by rational strategies of the refiners. Efficient production relied on hired work of settlers. Each bad harvest year made millions of destitute peasants without a plot of land to their name look for a job elsewhere. Residents of the less fertile provinces gravitated towards the black soil southern reaches of the empire, with their booming sugar industry. These people left their homes for years and years, traveling from one refinery to the next, ready to take up even the hardest jobs. A solicitor of Tereshchenko Society once wrote to his masters: “I sent two recruiters to hire workers. They write to me from the Voronezh province that, thanks to a crop failure, more than a hundred souls can be hired for a low wage.[2]" Besides, progress was kind to the magnates: new and improved technologies of beet processing made sugar refining less labor-intensive, allowing them to hire women and teenagers instead of men at much lower costs.

As a result, production rates were increasing, with beet fields covering ever bigger patches of Dnieper Ukraine. The streams of white sand would multiply, and soon the empire fell short on people capable of buying it. After all, refiners were reluctant to reduce prices and convert sugar into an easily available commodity. By the end of the nineteenth century, the Russian Empire was gripped by the first crisis of sugar overproduction, and for a number of years sacks of unsold "white gold" had been rotting at railway stations.

No man is an island

In an effort to cope with this crisis, the Tsarist government attempted to to encourage sugar exports to European countries. In order to compete with Western producers, the product had to be dumped at prices barely covering its production expenses. These losses were offset by the state that was endowing magnates with cash bounties and various incentives for exporting sugar. Thus sugar exports become an extremely lucrative business, causing a nationwide “gold rush”. European countries, in return, had to deal with bulk of cheap sugar coming from Ukraine, and reward their own production, adding fuel to the fire of the already overheated industry. The crisis of overproduction was gradually becoming global, with millions of tons of sugar piling up in warehouses. Concerned with these symptoms, European sugar-producing countries came up with a very special treaty, and signed it in 1902 in Brussels.

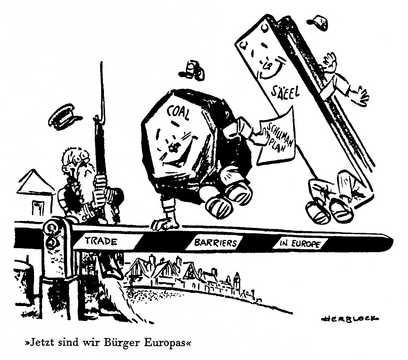

The Brussels Sugar Convention was a marvellous creation, well ahead of its time. It’s aim was to resist state protectionism and export regulations which distorted "natural" prices of the precious commodity, and locked manufacturers in a breakneck dumping race. To oppose such practices, the treaty masterminds formulated an ideal of "free trade"– the one to regulate the totality of global market[3]. After refusing to subsidize their exports, signatory countries shielded themselves with a tariff barrier from any neighbouring countries unwilling to play by the new rules. They were also seeking closer integration with one another, agreeing on common rules. The Permanent Commission of the Sugar Union gained unprecedented control over the individual countries' decisions on the fate of their industries. Many saw this as an encroachment on national sovereignty. There was an increasing concern that rules would be dictated by the sugar technocrats of Brussels, those evangelists of globalization and free trade. A familiar story, is it not? Indeed, many see this integration project as the forefather of the European Coal and Steel Community, later known as the European Union. However vaguely, it had outlined the walls of the future "fortress Europe".

Herblock, Now we are citizens of Europe, 1951

Unsurprisingly, The Russian Empire, with its syndicate monopolies and technically backward production, had to opt out from the newly established rules. In 1902, Ukrainian sugar was banned from the British markets for the first time. Having lost its European markets, which consumed half of the exports Russia had to turn to the new horizons. The arsenal of sugar diplomacy aimed at Central Asia and the Middle East and, a new focal point of imperial interest. Meanwhile, the population of tsarist Russia continued to pay the price for the games that syndicates were playing on the global chessboard. No matter what its grandiloquent statute may have said, the sugar syndicate’s one and only raison d'être was to support the artificially high sugar price on the national imperial market. Pulling their resources, the refiners began to artificially limit production and arbitrarily alter the price of “white gold,” guaranteeing themselves unprecedented profits.

At the same time, they exported cheap sugar to Europe, competing with much better equipped factories. “We’d rather go hungry than fail to export,” the saying went in those years. Indeed, Kyiv residents bought the sugar produced in Ukraine at thrice the price it got on the global markets. A unique occasion indeed, when the consumption of sugar in one of the largest exporting countries was much lower than in wealthy Britain. Cheap and affordable sugar was changing the whole notion of a Western European diet: consumption of snack foods is no longer to be vulgar, and the Dr. Pepper and Coca Cola beverages debut at the 1904 World's Fair. Meanwhile in Russia, population still starved for sugar, with the silent consent of the government and syndicates.

In pursuit of public benefits

In order to sweeten the bitter pill, the sugar magnates generously donated to charity and cultural causes. They founded, supported and renovated universities and colleges, schools and libraries, monasteries and churches, cultural venues, literacy foundations, music colleges and concert halls, conservatories and theaters, orphanages and hospitals. They were particularly supportive of art. Having got into the habit of art collection, they bought up artworks at exorbitant prices at Vienna, Madrid and Paris auctions. Thanks to the ambitious refiners, the masterpieces of the early Renaissance, the Spanish Golden Age and Dutch art had first found their way to Kyiv. New European currents, including the works of Gauguin, Cézanne or Matisse, did not escape their notice either. Thousands of works amassed in luxurious mansions of Tereschenko and Khanenko families eventually would become accessible to the public. Private exhibition halls would become art museums to rival their European counterparts.

Kyiv residents noticed the changes in the “sugar capital” with surprised gratitude. White gold, produced by hard work of millions of underpaid, exploited workers, was exported in a growing stream, but the revenue returned to the community in the form of public amenities and cultural treasures. Wasn’t it marvelous? The leading refiners, and the youngest descendants of the sugar dynasties in particular, became known primarily as philanthropists invested in the public good, and as devoted patrons of art. They established ties with the art milieu, organized auctions for their favorite artists, and became honorary members of art academies. It seemed they were doing their business almost reluctantly, as if driven by the desire for public benefit, rather their their own profit. The ties of mutual gratitude and patronage grew stronger over the years.

Obviously, this culture of competitive philanthropy was not a local invention, and was adopted from other sugar metropolises – primarily, from Great Britain. British industrialists, such as Henry Tate, enjoyed a long and passionate history of collecting artworks and displaying them to a select audience, often in their own premises. Later, Tate would open his treasures to the public and finance the construction of the gallery, which would become a prototype for museum collections of modern design. This entrepreneur would remembered as a man of exquisite taste, but also as a liberal mind, supporting a variety of undertakings in public education and religious freedom – with his word, as well as his coin.

“The Mother Plant”

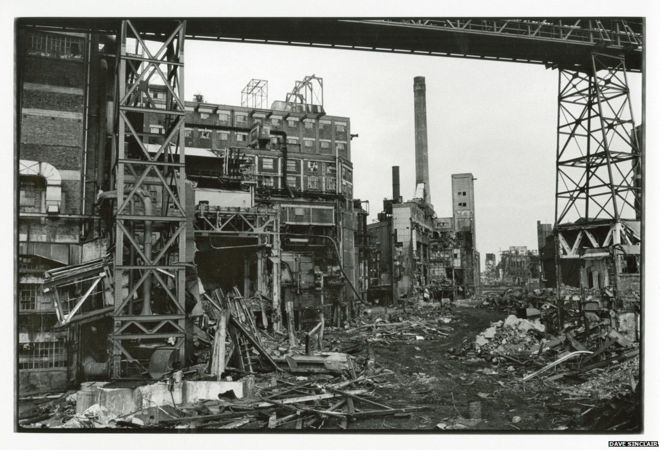

However, these cultural gains would easily drown in the agitated gamut of the late Victorian era - a time of market expansion and trade wars that revealed the fragile interdependence of the centre and the periphery. The contradictions were particularly evident In Liverpool, a city that had emerged through the cultivation of sugar cane, the "quintessential slave crop". By the end of the XXth century the snake of free trade bit itself by the tail - large sugar mills, once the landmarks of British industrial power, had been associated with unprofitability and social tensions. The probable reason could have been UK's accession to the European Economic Community, which meant easier of admittance for continental suppliers. Common agricultural policy of the EEC subsidized sugar beet production. Needless to say, this happened to a great misfortune of peripheral countries still dependent on sugar cane. One can sense a hint of cynicism in this combination of free-market rhetoric and local protectionism, in denying former colonies of their traditional markets. However, the world of white gold is no place for moral imperatives. The taxonomic distinction between beet and cane still marks the outlines of centre and periphery, belatedness and modernization, the first and the third world. No man is an island, though – a lesson learned by the one of former empires that was late to renounce sugar cane.

Demolition of Tate & Lyle refinery, early 1980s

The “mother plant” at Liverpools’ Merseyside, once a crown jewel of Tate dynasty, was finally decommissioned in 1981, nearly a hundred years after its founding. The threat of layoffs had been weighing on workers for decades. One and a half thousand families worked in the factory, often in three generations, from grandfather to grandson. Its closure punctured a hole in the community - a point of spatial and emotional devastation. Ron Noon, a labour movement historian, cites the testimony of John McLean, a union leader known as the Scribe: "part of the structure of the city is being thrown to the wolves in the name of profit, in the name of the Common Market, and in the name of very greedy people"[4]. Interestingly, the one who dared that to break the spine of this creature was none other than Thatcher’s Minister of Agriculture, one of the directors of Tate & Lyle. However, it didn’t go down without a fight. Trade union movement of Merseyside workers, though ended in a "glorious defeat", is remembered for many examples of organized resistance and solidarity. It provided materials aplenty to historians willing to explore the bitter experiences of the working class in Thatcherist Britain. Ron Noon himself organized a special "celebration" to commemorate the 25th anniversary of first redundancy notices being issued to the workers. This memorable event was attended by former factory employees, many in their twilight years, and was supported by Tate & Lyle[5]. Later, a documentary film on the union’ struggle was screened at several institutions, including Tate Liverpool, a contemporary art gallery located in the harbor on the banks of the River Mersey.

–

[1] http://cargocollective.com/lozovoy/beetroot-revolution

[2] Панкратова. A.М. Пролетаризация крестьянства и ее роль в формировании промышленного пролетариата России (60-90-е годы XIX в.) // «Исторические записки», № 054 (1955). – М. : Издательство Академии наук СССР.

[3] Fakhri, M. Sugar and the Making of International Trade Law. – Cambridge University Press, 2014.

[4] Noon, R. 30 years ago TODAY, 90 day Redundancy Notices were served on Love Lane Refinery workers // Love Lane Lives, January 22nd 2011

[5] Noon, R. A Bitter Sweet Public History Project // Love Lane Lives, October 27th 2019

–

Images:

Leon Wyczółkowski, Beet Harvest I, 1893 (Source)

Herblock, Now we are citizens of Europe, 1951 (Source: The Washington Post. 25.03.1951. Washington. Copyright: (c) The Washington Post)

Demolition of Tate & Lyle refinery, early 1980s. (Photo © Dave Sinclair. Source 1, Source 2)

–

Translation: Iaroslava Strikha, Larion Lozovoy

–

Larion Lozovoy is an artist and researcher living in Kyiv. He is focusing on economic history of Central-Eastern Europe, ideologies of modernization and creativity.

–